In A Dream Foreclosed, journalist and activist Laura Gottesdiener highlights four people threatened by the loss of their homes; discusses racism and predatory lending; and challenges old ideas about property and private housing.

In the orgy of subprime lending that created the great recession, and the subsequent foreclosures and evictions that followed, African Americans have suffered disproportionately. Statistics tell one side of the story. Minorities with good FICO scores, says the Center for Responsible Lending, ended up with high-interest loans at three times the rate as whites with the same scores. Borrowers of color are more than twice as likely to lose their homes as white borrowers.

But why? Gottesdiener explains. Starved of mortgages when their own neighborhoods were redlined, barred from suburbs by racially restrictive covenants, many blacks became the targets of predatory lenders once those practices were toppled. Loan pushers peddled to black churches, blitzed black neighborhoods with ads, and bumped black borrowers over to high-interest, high-risk loans—including people who qualified for better ones. Wells Fargo’s computer software even provided an option to send information written in “African American”—a bizarre linguistic detail supplied by a whistleblower.

But why? Gottesdiener explains. Starved of mortgages when their own neighborhoods were redlined, barred from suburbs by racially restrictive covenants, many blacks became the targets of predatory lenders once those practices were toppled. Loan pushers peddled to black churches, blitzed black neighborhoods with ads, and bumped black borrowers over to high-interest, high-risk loans—including people who qualified for better ones. Wells Fargo’s computer software even provided an option to send information written in “African American”—a bizarre linguistic detail supplied by a whistleblower.

Cushioned by the knowledge that they’d be selling off the loans, lenders did not play fair. They presented borrowers with opaque applications and contracts: Alan Greenspan himself has reportedly called some loan documents incomprehensible. Lenders lied about terms, hiding things like lump-sum payments no borrower would have agreed to. They even foreclosed on people who were current on their payments.

Then, too, “sleazy, greedy, and flat-out fraudulent” mortgage-servicing companies contributed to the screwings-over. The author profiles Griggs Wimbley, a North Carolina man with a business degree who took out a construction loan for a new development. Soon after his loan was packaged and sold, a servicing company claimed he’d missed a payment. Wimbley faxed them proof to the contrary, but soon faced foreclosure. He fought back—again and again. For 10 years, Wimbley fended off foreclosure notices while gathering hard evidence of fraud.

These companies often hounded borrowers with illegal fees, deliberately delayed posting on-time payments, and robo-signed foreclosure affidavits without regard to the facts of a loan’s history.

It is not hard to feel outrage on Wimbley’s behalf; even with his education and resources, he got taken for a terrible ride. But in trying to make sense of the mortgage crisis, many people assume that irresponsible borrowers, who shouldn’t have agreed to loans they couldn’t pay off or didn’t understand, were at fault. Gottesdiener’s spotlight on the egregious business practices of mortgage-pushing and mortgage-servicing companies does an important service by putting the blame back where it belongs.

Given that evictions damage neighborhoods and cost cities so much money, shouldn’t we question the primacy of bankers’ contract rights over the broader social contract?

There are moments when Gottesdiener’s journalistic sobriety gives way to activism, as when she describes eviction blockades as “utterly magical” and refers to a presidential speech at a White House Conference on Minority Homeownership as “advertising to lure new customers” to the loan industry. Also, in explaining that much of Detroit’s “abandonment” by homeowners was involuntary, the author suggests that the city’s (then-impending) bankruptcy was driven by foreclosures when in fact the causes are more complex.

Gottesdiener is at her best when discussing the big picture. Given that evictions damage neighborhoods and cost cities so much money, she asks, shouldn’t we question the primacy of bankers’ contract rights over the broader social contract? Perhaps for-profit housing is a failed model. Perhaps housing is a human right. And her fascinating and lyrical discussion of the historic links between property ownership and personhood—a history loaded with injustice for African Americans—leaves the reader wanting more.

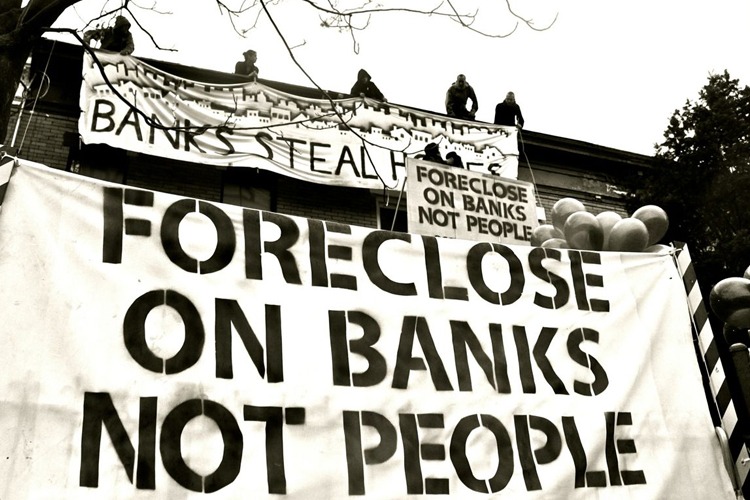

A Dream Foreclosed is also about the power of resistance. Gottesdiener describes people rendered homeless by the exigencies of the housing system as “capitalism’s refugees,” then shows that such refugees are far from powerless.

After moving her family from shelter to couch to car seat, a Chicago mother with three little girls and a boy “liberates” a foreclosed and abandoned house. A Tennessee man helps fend off the developer threatening his home in the projects, where he has lived independently since recovering from a grim accident. An elderly Detroiter and her neighbors physically block evictors until bad press convinces the bank to sell back the house. Wimbley joins a group of activists; his county clerk agrees not to sign off on his eviction.

While triumphant, these endings seem precarious and temporary, leaving the reader uneasy.

We should be worried. Racism is but one manifestation of a system that privileges sales figures and interest earned by lenders over human lives, and meaningful change that puts people first will call for more such compassionate and galvanizing dispatches from the front lines. Ten million foreclosures are a statistic. Four homeless children are a tragedy.

Jenny Blair is an M.D. and writer.

0 Comments