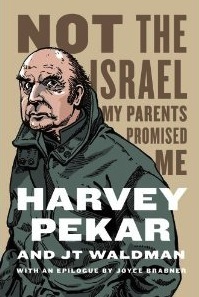

Reviewed: Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me by Harvey Pekar and JT Waldman (Hill and Wang, 176 pp., $24.95). There are several reasons Harvey Pekar’s posthumous screed, Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me, might spark discomfort.

Reviewed: Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me by Harvey Pekar and JT Waldman (Hill and Wang, 176 pp., $24.95). There are several reasons Harvey Pekar’s posthumous screed, Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me, might spark discomfort.

The underground-comic writer’s books themselves are always uncomfortable, both in their lack of “coolness” and in the roughness of their humor on the soul.

The subject, additionally, is a thorny one: As Pekar and his illustrator, JT Waldman, ramble through Cleveland, Pekar articulates his profound dissatisfaction with Israel’s actions in the latter part of the century. The centuries-long backstory of the Jewish people’s beginnings and subsequent struggles have found a good teller in Pekar—but at times, the text smacks of a rant. And Waldman’s illustrations, beautiful as they are, don’t always mesh with the plainness of Pekar’s language.

Two impulses clash here: One is the presentation of the story of Jewish history, and the other is the impulse to show Pekar’s Cleveland at its most poignant. The two parts couldn’t be more opposite. The patter between bursts of historical data shows Pekar at his irascible best—screaming at a used-bookstore worker who isn’t as gripped by historical stories as Pekar is, showing indifference when Waldman makes Tolkien references that elude him, or choosing an upscale food market rather than fast food when Waldman offers to pay for lunch.

When the book addresses history, however, other voices take over the text—dates, pictures of famous historical figures, little bits of mock dialogue among cartoon-like emblematic individuals—as if they’re from a different source altogether. Though deft, these additions make one long for less lecturing and more of the food markets and gloomy, crumbling buildings of Cleveland.

Though Pekar’s views are articulated intelligently, the book doesn’t make the impossibility of its project seem less so. Pekar (who died in 2010) had been a skeptic about Israel since the ’50s; an editorial he wrote in the ’70s protesting the Israeli invasion of Lebanon provoked an angry written response from one of his own relatives. And yet, as the writer states repeatedly, he does not consider himself a “self-hating Jew” by any means, just one with a conscience.

In order to understand what that conscience is reacting to, though, two stories have to be told—the story of Pekar’s race and that of his life as a member of that race. From the Jews’ ancient conflicts with the Romans in Jerusalem; through hundreds of years of wandering between the Middle East and Europe; through the horrors of World War II; and then through the Arab-Israeli conflict, with its endless acts of aggression on both sides, Pekar tells the facts as he sees them, eloquently and clearly. He himself grew up in a highly Zionist home, in which, as he tells it, there was “no room for debate” on the question of a Jewish homeland in Israel.

The narrative of Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me demonstrates that, as Pekar matured, he increasingly viewed Israel’s militancy and violence toward the Palestinians as unfair to a people who, as he puts it, “are not going anywhere.” But the issue is, to understate things, complex, and this book is too brief to flesh out its complexity adequately.

The artwork gives shape to the arguments. Waldman’s meticulous and versatile drawings mutate memorably to suit the text they illustrate, as when the frames spiral across page spreads to mimic the pair’s meanderings through Cleveland. Nevertheless, in this collaboration, as in so many other collaborations with Pekar, the illustrations don’t quite fit the text. Invariably (with the glaring exception of R. Crumb), Pekar’s collaborators are dwarfed by the gravity of Pekar’s seriousness and grim view of the world. Here too, Waldman’s skill and facility seem at odds with Pekar’s striving for clarity and ordinariness, which would seem to slough off craft.

Still, perhaps the very ornateness of this book is the kind of memorial Pekar, and his worldview, deserve.

Max Winter is a poet and critic whose reviews have appeared in Bookforum, The New York Times, the San Francisco Chronicle, and elsewhere. He is the author of the book The Pictures; his second book, Walking Among Them, is forthcoming from Subpress.

0 Comments