Once upon a time in Italy, a prominent citizen declared: “It is unacceptable that sometimes in certain parts of Milan there is such a presence of non-Italians that instead of thinking you are in an Italian or European city, you think you are in an African city.”

In case the message was not crystal clear, he then spelled it out: “Some people want a multicolored and multiethnic society. We do not share this opinion.”

The citizen in question was none other than Silvio Berlusconi: billionaire three-time Italian prime minister, intermittent convict, and head of a superpowerful media empire, who, as the New York Times put it in January 2018, has now “cleverly nurtured a constituency of aging animal lovers—and potential voters—by frequently appearing on a show on one of his networks in which he pets his fluffy white dogs and bottle-feeds lambs.”

Panic over the devolving color-scape of the patria is, of course, of a piece with the greater right-wing narrative of Fortress Europe, which shuns the possibility that centuries of European plunder and devastation of the African continent might have any bearing on current migration patterns. But while history lessons may not be as entertaining as lamb-nursing sessions or bunga bunga parties, it’s worth noting that, in the not-so-distant past, Italians voluntarily found themselves in many African cities—and for purposes far less dignified than trying to survive.

In The Addis Ababa Massacre: Italy’s National Shame, published by Oxford University Press, for example, author Ian Campbell explains that the Italian military occupation of Ethiopia (1936–41) was “underpinned by a policy of terror” and entailed a three-day bloodbath in February 1937 by Italian militants and civilians that wiped out—by Campbell’s estimates—some 19–20 percent of the Ethiopian population of Addis Ababa. A 2017 post on the Brookings Institution website furthermore recalls such highlights of Italy’s colonial adventures in Libya as the internment “in a dozen concentration camps” of 10,000 or so civilians from semi-nomadic tribes.

While the Berlusconian warning re: the creeping Africanization of Italy’s northern metropolis was issued back in 2009, more recent years have also produced a deluge of xenophobic rhetoric courtesy of the Italian political élite. During an ultimately successful candidacy for the president of Lombardy in 2018, Attilio Fontana alerted Italian radio listeners to the existential threats posed by that most awful of phenomena known as immigration: “We must decide whether our ethnicity, our white race, our society should continue to exist or should be erased.”

This same campaign season saw Matteo Salvini—who subsequently acquired the posts of Italian interior minister and deputy prime minister— freak out about the “Islamic presence” in the country, which had resulted in a situation in which “we are under attack; at risk are our culture, society, traditions, and way of life.”

Credited with sounding the alarm on the Islamic attack was the late Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci, thanks to whose increased radicalization post-9/11 we learned of Muslim schemes to replace European mini-skirts with chadors and cognac with camel’s milk. Excoriating U.S. universities for permitting persons named Mustafa and Muhammad to study biology and chemistry despite the danger of germ warfare, Fallaci additionally threatened in 2006 to explode a mosque and Islamic center slated for construction in Tuscany—an ironic solution, no doubt, to the issue of terrorism.

Upon assuming his offices, Salvini wasted little time getting down to business. Having pledged to deport half a million migrants as part of his vision of a “mass cleaning” of Italy—which would be carried out “street by street”—Salvini declared Italian ports closed to migrant rescue vessels, a move barely distinguishable from mass murder, given such summer 2018 headlines as “Mediterranean: more than 200 migrants drown in three days.”

The minister also announced plans for a census of Italy’s Roma community in order to expel non-Italian members, despite reminders from human rights groups that an ethnicity-based census was not exactly legal and was furthermore reminiscent of the behavior of Benito Mussolini.

I, on the other hand, continue to be permitted access to Italian territory any which way I please on account of my own acceptable skin color and passport, an arrangement that has enabled me to spend a part of each summer in the southern region of Puglia without risking maritime death or street-cleaning.

So, too, has it offered me a glimpse of the frontline in the great battle for Italian culture and homeland in the face of camel’s milk and similar plots.

***

My inaugural visit to Puglia took place in the summer of 2004, when Amelia and I briefly parted ways after our first round of avocado packing in Spain and doing nothing much of anything in Turkey. A boy named Gianluca from the town of Oria in the heel of the Italian boot—with whom I was conducting a not-extremely-scrupulous long-distance relationship based on approximately two encounters—invited me to his territory while Amelia paid her annual visit to the U.S. to avert the confiscation of her Green Card. Though our relationship was eventually officially downgraded to friendship, it was made clear that I was still part of the family and would forevermore be force-fed as such.

Gianluca’s father had passed away some years before, leaving Gianluca’s mother Adriana to care for la nonnina—her mother-in-law—who by the time I entered the picture already spent most of the day confined to the bed yet still managed periodic shrieks, lest anyone in the vicinity become too comfortable. Other attention-generating methods included hallucinating a string of lovers in hot pursuit of Adriana and shouting for the priest, as well as halfheartedly attempting suicide with household items ranging from a hammer to a window curtain. In each case, crisis resolution took the form of the usual barrage of Italian penis- and testicle-centric curse words, followed by yet another plate of pasta slammed down in front of la nonnina.

Located just east of Taranto and half an hour from the Ionian Sea, Oria is organized around a castle built by crusader and Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. Legend has it that the town owes its continued existence to a benevolent intervention by Saint Barsanofio, who summoned cloud cover one fine day during World War II and thereby thwarted a planned bombing raid.

In keeping with the Italian tradition of evacuating the cities for the coast in times of infernal heat, Adriana & Co. moved each summer to her plot of land by the sea, which features a small house off a dirt lane. Off the same dirt lane are the respective summertime abodes of Adriana’s four siblings. Olive trees and grapevines abound. The address, as far as I have been able to determine, is: “Turn left after the twelfth utility pole after the first bridge on the main road leading from the closest seaside hamlet.”

When la nonnina ultimately perished of natural causes and Gianluca and his brothers—all of whom lived elsewhere in Italy—curtailed their visits to Puglia, I ended up with my own room at the beach house, where I spent many summer nights partaking of one-euro liters of wine and serving as captive audience to Italian homicide TV shows, opiate of the Italian masses. Supplementary entertainment was provided by a steady stream of visiting relatives, each of them committed to sustaining an ambience of cacophonous drama and well versed in the art of Italo-gesticulation, thanks to which even the most banal of discussions about inflatable mattresses or plastic cups became a lively spectacle.

One recurring theme, to be sure, was migration, about which everyone was pretty much in consensus but nonetheless still needed to shout about. Initially, migrants were often referred to collectively as marocchini—which could apply to anyone from Morocco to Sudan to Bangladesh—and blamed for creating all manner of trouble in casa nostra when they should have stayed put in casa loro. Shot down were all attempts by me to interject details about real live marocchini—such as Abdul, who had hosted Amelia and me for numerous months in southern Spain; Abdul’s family, who had hosted us in Morocco itself; and the surplus of Moroccans who had picked us up hitchhiking and were in fact generally the only demographic that picked us up in Spain aside from intoxicated Spaniards returning from the disco on weekend mornings.

As the Puglian discourse grew more sophisticated over the years, Italy-bound refugees and migrants graduated from being uniformly Moroccan but remained uniformly viewed as thieves, rapists, and killers—though proof of such behavior was never forthcoming. Another common complaint had to do with the notion that hard-earned taxpayer money was being flung at each and every individual who happened to wash up on Italian shores, to be squandered on luxury hotel accommodations, the latest cell phones, and whatever other goodies the lazy and opportunistic refugee heart might desire.

Obviously, the channeling of public attention and wrath toward the “Other” is a handy distraction from institutionalized corruption in Italy, whereby members of the ruling class fling hard-earned taxpayer money at themselves. And the process is rendered all the more fluid when the media is dutifully standing by to provide the proper talking points.

Consider an item on the website of Italy’s Il Giornale newspaper—published by Berlusconi’s very own brother, who in 2016 valiantly defended the paper’s decision to distribute copies of Mein Kampf—advising that “Italy IS NOT an Islamic country,” despite the best attempts of “he who invades me trying to expel me from my land” and “he who wants to take me a thousand years back to when the Moors landed . . . on my shores to rape and kill.”

As is the case in U.S. propaganda starring Muslims and Mexicans as invaders, rapists, and murderers, the decisive Western monopoly on destructive activity in the opposite direction is conveniently lost in the equation. Afghanistan and Iraq come to mind, where U.S.-led kill-fests boasting Italian participation have not in the least bit mitigated presumptions of the inviolable sanctity of U.S. and Italian borders, respectively.

In my meanderings through Italy, I have inevitably come across some of the miscreants intent on sabotaging the chromatic composition of the Italian homeland. In 2015, I spoke with a 20-something-year-old Eritrean migrant in Rome who went by the name of Jerry and who had fled his own torture-prone homeland two years previously, thus extricating himself from eternal military service.

While Italy had of course felt no qualms about helping itself to the colony of Eritrea back in the day, Jerry quickly assumed the position of persona non grata alongside his fellow itinerant Eritreans in Rome, where he had taken up residence in an abandoned office building near the city’s central train station (i.e. the luxury accommodations detected by the Puglians) and had begun offering informal English lessons as a means of not starving.

Reflecting on whether or not it had been worth it to risk his life traveling from Eritrea to Ethiopia to Sudan to the migrant torture-rape-kidnapping-slavery hotspot of Libya—spending three weeks in the desert and then four days crossing the Mediterranean in a storm while trapped in a tiny vessel with 300 other people—Jerry concluded that, in terms of hope for the future, he was still pretty much where he had started.

Also in Rome in 2015, I paid a visit to the Baobab center in the Tiburtino neighborhood, which catered primarily to Eritrean migrants transiting to northern Europe. Although designed to shelter fewer than 200 people, the center was reportedly often packed to over four times its capacity. On the day of my visit, the guests included a sobbing young woman who had just been informed that her brother had been kidnapped while attempting his own migration.

The following year, I again found myself among uprooted Eritreans, this time many thousands of kilometers away, in a refugee camp in Ethiopia, another country my passport and I were able to access with incredible ease—since just because Africans had to jump through lethal hoops to exit their continent didn’t mean white people shouldn’t be able to go on safari at the drop of a hat. I myself did not undertake any activities involving wildlife, although I did visit the Addis Ababa tomb of Ethiopia’s last emperor, Haile Selassie, as well as consume an inordinate quantity of pineapple pizza. My Lebanese boyfriend was also in attendance, but was posing as a Venezuelan in light of Lebanon’s notoriety in the region as a living hell for Ethiopian and other migrant domestic workers.

From Addis we embarked on a two-day bus ride north. Acquiring bus tickets was almost as much of an adventure as the trip itself given the intricacies of the Ethiopian calendar—according to which it was then 2008—and the timekeeping system, according to which, if it was 10 a.m. everywhere else in the East Africa Time Zone, it was 4 a.m. in Ethiopia.

In the northern Ethiopian town of Shire, not far from the Eritrean border, I had an arbitrary acquaintance in the form of an Irish freelance journalist I had met the previous year at a conference in Tehran to which I had accidentally been invited. This dapper gentleman was married to an Ethiopian woman, delighted by his purchasing power in Ethiopian birr, and, it seemed, the talk of the town (for an approximate visual, think Willy Wonka in Africa).

He kindly introduced us to the prime beer-drinking spots in Shire as well as to an American representative of a European humanitarian NGO operating in the town, who confirmed that his organization was actually receiving big bucks from ultra-right-wing European entities concerned with curbing the northward flow of refugees and migrants. Humanitarian, indeed.

While the NGO-er insisted that I’d never be granted authorization to enter the Hitsats refugee camp—located in a desolate area about an hour from Shire—the obstacles proved not so insurmountable, and my boyfriend and I were escorted there one afternoon by the proprietor of our hotel, where we were the only guests and which may or may not have been a money-laundering front.

The proprietor was a middle-aged Sudanese man who explained to us that he had gone from being an orphan in Khartoum to being a driver in Saudi Arabia for some component of the royal family to striking it rich with the help of his Saudi patron, who had suggested that he invest in gold. What business he may have been contemplating in Hitsats was never revealed, but he took a number of photographs of a small church rising from the heat and dust, where we stopped to chat with a group of barefoot refugees, some of them sporting Eritrea soccer shirts, as they went about painting the façade of the structure.

One member of the group outlined his own reasons for fleeing Eritrea, which, as with Jerry in Rome, had to do with forcible and unending military service that was tantamount to slavery. Following eight years of army life and no end in sight, the man had escaped to Ethiopia in 2015 and had yet to communicate with his mother, whom he feared had been punished for his transgressions. He had now entered into indefinite limbo in Hitsats, lacking the funds for onward travel. The cheapest price tag he’d heard for being smuggled to Greece, he said, was around $5,000—i.e. over nine times the per capita annual income in Ethiopia at the time, according to the World Bank’s calculations.

By coincidence, around the same time that I was visiting Hitsats, Thomas Friedman had also descended upon Africa to explain things about migration. This was a continent he rarely managed to visit, despite his self-declared unlimited travel budget courtesy of the New York Times. The occasional previous descent had enabled such impressive journalistic feats as a 121-word description of a leopard eating an antelope in a Botswanan tree in 2009.

Predictably titled “Out of Africa” and “Out of Africa, Part II,” Friedman’s April 2016 intervention took him to “the headwaters of the immigration flood now flowing from Africa to Europe via Libya,” which—along with the “refugees fleeing wars in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan”—had created “two flows pos[ing] a huge challenge for the future of Europe.” The upshot, in Friedman’s view, was that “we have to help [the Africans] fix their gardens because no walls will keep them home.”

While the average innocent reader may have been hard-pressed to determine how the gardening solution factored into the picture when gardens were not mentioned anywhere else in the two-part series, it goes without saying that someone who has devoted his life to promoting the capitalist destruction of the globe is not exactly the most qualified candidate for African gardener. It furthermore bears reiterating that Friedman had also valiantly championed the very refugee-producing wars now challenging the “future of Europe.”

As journalist and author Matt Taibbi once commented with regard to Friedman’s schizophrenic bid to reinvent himself as an environmentalist:

Where does a man who needs his own offshore drilling platform just to keep the east wing of his house heated get the balls to write a book chiding America for driving energy inefficient automobiles? Where does a guy whose family bulldozed 2.1 million square feet of pristine Hawaiian wilderness to put a Gap, an Old Navy, a Sears, an Abercrombie and even a motherfucking Foot Locker in paradise get off preaching to the rest of us about the need for a “Green Revolution”?

Moral of the story: perhaps Friedman should focus on fixing his own garden first.

***

In the meantime, the African garden has produced plenty of tales of rootlessness and exile far less frivolous in nature than my own.

In the Maltese town of Birżebbuġa in 2014, for example, I made the acquaintance of a young Gambian man by the last name of Manneh, who, like many migrants, had ended up on the island of Malta by accident while trying to reach Italy by sea. Facing a lack of sustainable employment options at home, Manneh had slowly made his way from Gambia to Libya and then boarded a small vessel with more than 120 other people to cross the Mediterranean.

Four days later the passengers had run out of food and water and the boat had acquired a leak, at which point it was intercepted by a U.S. warship, which handed the human cargo off to the Maltese. In keeping with Malta’s policy of mandatory detention of migrants, Manneh was interned for several months at the Safi detention center, located on an army base; in case there remained any doubt about his fundamentally criminal identity, even visits to the hospital required him to be put in handcuffs.

Offering to accompany me by public bus to the nearby Maltese capital of Valletta, Manneh pointed out key landmarks such as the so-called immigration reception center near Birżebbuġa where he had been transferred once it had been decided that he no longer needed to be detained full-time. At the center he slept in a small trailer referred to as a “container” with seven other persons. He drew attention to cement pipes situated around the establishment’s perimeter, inside which migrants who had been expelled from the center had taken up residence.

Human rights lawyer Neil Falzon, director of the Malta-based human rights foundation Aditus, speculated that the reason Malta insisted on implementing what he described as “the most expensive, forceful, and harmful migration management regime” had to do with the government’s “need to be perceived as a strong and controlling force.” He told me that the fanatical detention scheme, which didn’t even spare young children, was presented to the Maltese public as necessary for “national security [and] social order” and was justified via regular “reminders of invasion, terrorism, disease, and over-population.”

Indeed, the government’s approach seemed to have paid off, as another Gambian I met in Birżebbuġa reported having nearly had the police called on him for daring to say hello to someone in the street. Of course, other varieties of foreigner were more than welcome in Malta—such as those to whom the government was then aiming to sell European Union passports for 1.15 million euros a pop.

Like Italy, Malta has expended much energy whining about its disproportionate refugee burden and endeavoring to wrest the role of victim from the refugees themselves. But while European governments exempt themselves from humanitarian standards by arguing that intimidating refugees in fact helps save lives by deterring migration, intimidation is ineffective when people have nothing to lose. And as long as the prevailing economic system depends upon borders that apply to have-nots but not to predatory corporations or the ubiquitous U.S. military, migration patterns will hold.

In 2015, I visited some of the informal tented settlements for Syrian refugees in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley. There, an older Syrian man from the city of Homs noted that an increasing number of young people in his camp were trying their luck with what he called the “boats of death” to Europe—his two sons included, from whom he’d had no news since they’d departed Lebanon. The risks of this passage were immaterial, he said, because the refugees saw themselves as essentially dead already. Another group of Syrians responded to the question of how they envisioned the future by placing their hands over their eyes: “We cannot see anything.”

On my annual summer excursion to Puglia in 2018, the Italians had amassed more trivia re: the migrant scourge. They filled me in one evening around the plastic table on Adriana’s patio near the coast, where an assortment of relatives gathered amidst the deafening song of the cicadas and a swarm of repellent-resistant mosquitoes. Once the usual topics had been covered—the malevolent euro, the geriatric cousin whose savings were being rapidly appropriated by a much-younger seductress, the thieving bastardo poultry vendor in a neighboring village whose hens refused to lay eggs, the three Neapolitans who had disappeared in Mexico and become instant stars-in-absentia of the Italian TV homicide programs—it was the migrants’ turn. Thanks to the ensuing raucous symposium, conducted half in Italian and half in dialect, I learned that the Italian governo di merda had stooped to new lows in its obsequiousness vis-à-vis Italy’s foreign guests, who were now getting steak feasts while the native population was forced to survive on tomatoes and bread.

Following a brief detour into a debate over whether tomatoes and bread might not in fact be preferable as well as reminiscent of the good old postwar days when life was much simpler, the governo di merda was unanimously proclaimed to have become less merda with the ascension that year of minister Salvini, vanquisher of migrants, Roma, and whatever other Others might be lurking.

Salvini, incidentally, was also the head of the political party known until recently as the Lega Nord—Northern League—before the “Northern” qualifier was dropped to accommodate right-wing maniacs in central and southern Italy, as well. Given the traditional disdain in the more prosperous and organized Italian north for anything southern, the potential for nationwide solidarity in the face of the refugee assault was no doubt heartening.

My Puglian interlocutors were additionally sympathetic to the border battle being fought in my own homeland, and concluded that—as had been demonstrated by the fate of the Neapolitans—Mexicans were obviously also criminals.

***

In May 2017, I took an overnight ferry from the Italian port of Civitavecchia to the Tunisian capital of Tunis to see my American friend Max, who was in the process of extending for as long as conceivably possible his PhD research. The Civitavecchia-Tunis ferry was preceded by an overnight Barcelona-Civitavecchia ferry, during which I slept in a chair in a large room with various Muslims intent on destroying Europe from within by playing the call to prayer on their cell phones. Also on board was a horde of Spanish high school students conducting an interminable dance party on the deck, on account of which experience I definitively entered misanthropic old age.

The second ferry contained a parasitic Italian who was en route to a seaside resort in Hammamet because Tunis was too smelly. He wagged his finger at me upon learning that Lebanon was my post-Tunisia destination: “È rischioso.” I eventually disentangled myself from his company and relocated to the cafeteria, where a Tunisian man promptly pitched his blanket next to my table and offered me water, soda, canned sardines, and aspirin—in other words, all of the ingestible materials he had on hand. Having manically stockpiled wine at the port, I was already set.

The man was on his way home for a visit from the northern Italian city of Ancona, where he had worked in a plastic factory for the past 15 years. At first he was upbeat about everything—Ancona, plastic, sardines—but then he confessed to me that he often questioned his decision to abandon his village near the Tunisian-Algerian border for the economic temptations of Italy, where, he declared, there was little proper food to be found, contrary to popular belief.

In the village his family grew everything necessary for human nutrition and happiness, he said, as he launched into a crash course on the beauty of bread-making. For his wife and three children, who continued to reside in the village year-round, he was bearing gifts of motor scooters and kitchen equipment, all packed into his Fiat Panda aboard the ferry. He inquired after my own marital status and pronounced himself overjoyed that my ragazzo was Arab.

The theme of food sovereignty would come up again when Max and I flew to the Tunisian island of Djerba to rendezvous with his comrade Habib Ayeb, a Tunisian geographer, academic, and documentary filmmaker based at the University of Paris VIII in France. The first attempt at takeoff by the notorious Tunisair ended when the plane careened down the runway only to execute a 180-degree turn and arrive back at the terminal. We dismounted and were loaded onto another plane, this one by the name of Hannibal.

The receiving line at the tiny Djerba airport included a surplus of heavily armed black-clad men in balaclavas, a testament in part to Tunisia’s ISIS problem—which, to be sure, was nothing that couldn’t be resolved with a little military assistance from the United States, a.k.a. the very entity that had assisted the rise of ISIS in the first place. Additional U.S. contributions to the Tunisian homeland became apparent as Ayeb showed us around Djerba and other sections of southern Tunisia, providing politico-economic interpretations of the striking landscape.

Despite the overabundance of olive orchards and the centrality of olive oil to the Tunisian diet, Ayeb lamented, the substance had become prohibitively expensive for many families. Luckily, the American outfit euphemistically known as USAID was on hand as usual to endow the suffering of the developing world with a façade of progress. As of the summer of 2017, the top “success story” on the USAID website’s Tunisia page was a short report from 2013 titled “Tunisian olive oil finds a new gourmet market,” celebrating the attendance of eleven Tunisian olive oil companies at New York’s Fancy Food Show that year.

This mind-blowing success was naturally attributed to USAID itself, which in the aftermath of Tunisia’s revolution of 2010-11 “began working with local [Tunisian] partners on a broad range of economic development programs to address some of the underlying causes of the revolution: high unemployment, lack of opportunities, and barriers to economic growth.” And voilà, the miraculous one-step solution to socioeconomic inequality and all other ailments: a gourmet export market that actively prevents poor people from consuming the things that grow on their land.

Ayeb’s 2017 documentary Couscous: Seeds of Dignity further exposes corporate-capitalist agricultural policies in Tunisia that obliterate any prospect of food sovereignty under the guise of “development.” In the film, Tunisian farmers speak with eloquence, humor, and dignified rage on such subjects as the calamitous invasion of imported seed varieties that proved far less resilient than local ones and resulted in subpar harvests, diminishing flavor and nutritional value, and a proliferation of seeds with nonrenewable traits—i.e. ones that can’t be replanted and must instead be continually repurchased from the supplier. So much for sustainability.

Also spotlighted is the toxic reliance on imported pesticides and chemicals required for the maintenance of non-indigenous seeds. One especially animated character—named, as irony would have it, Eisenhower—denounces “the West’s strategy” to dominate markets, to keep Tunisia “ever under their heel,” and in fact to “kill our agriculture.” Eisenhower’s verb choice would appear to be particularly appropriate given the track record of Western agribusiness deities like the U.S. biotech giant Monsanto, which has undertaken the task of dousing the planet with its signature herbicide Roundup while also presiding over country-specific feats like helping to set off an Indian farmer suicide epidemic (speaking of killing, prior to its reinvention as a “sustainable agriculture company,” Monsanto served as Vietnam war-era manufacturer of the lethal defoliant Agent Orange).

And while the West purports to hold the keys to the future, it’s also intent on perpetuating the past; as scholar Corinna Mullin, then a visiting assistant professor at the University of Tunis, remarked to me, Tunisia’s post-colonial period happened to entail “many structural continuities with the forms of accumulation and dispossession that characterized French colonial rule,” which ended in 1956.

Nowadays, she said, continuity is “manifested in ongoing forms of extractivism” that have been encouraged and facilitated “by international financial institutions, the EU, the U.S. and other prominent (neo)colonial-capitalist actors” concerned with pushing “neoliberal ‘development’ . . . for the benefit of international and a segment of local capital.”

In our final stop before returning to Tunis, Ayeb accompanied Max and me to the southern coastal city of Gabès, a hub of corporate exploitation that boasts the world’s only—rapidly dwindling—coastal oasis as well as the distinction of being Tunisia’s cancer capital. Presumably, this has something to do with the city’s industrial zone, which comprises phosphate refineries and other poisonous for-export operations that have been known to generate “clouds of rotten-smelling yellow gas” as well as tons of radioactive waste dumped into the sea.

The three of us stayed the night in Gabès at a home shared by several brothers and their families, who arranged cushions for us on the cement floor and served up a colossal mound of couscous. One of the children, a girl not yet two years old, was covered from head to toe in splotchy rashes that her parents said had been written off as “normal” by each of the four doctors that had been consulted—another casualty, perhaps, of killer development models.

The next morning, our drive back to Tunis was accompanied by a tyrannical wind that caused trash and dust to fly and swirl around the vehicle. Before Ayeb had the chance to name the phenomenon, I recognized it from Italy: the scirocco, defined by Encyclopedia Britannica as “a hot, very humid, and oppressive wind, blow[ing] frequently from Africa and the Middle East.” Indeed, one could always tell the onset of the scirocco in Puglia by a feeling of massive stupidity and agitation—not to mention the desire to suspend one’s entire existence until the wind had blown its course.

In a world defined by borders, it seems oppressive winds know none.

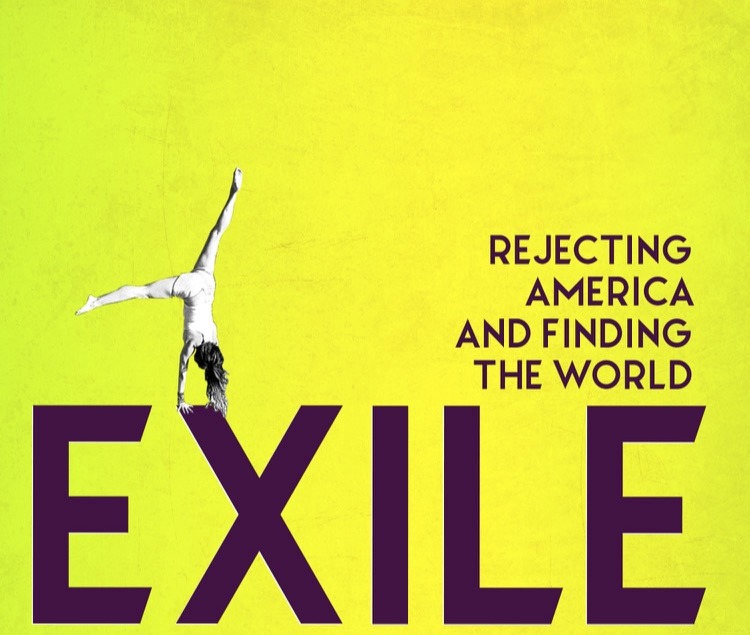

Belén Fernández is the author of Martyrs Never Die: Travels Through South Lebanon, published by Warscapes, and The Imperial Messenger: Thomas Friedman at Work, published by Verso. She has written for The Washington Spectator on a range of countries from Honduras and Columbia to Turkey and Ex-Yugoslavia. This article is excerpted from Exile: Rejecting America and Finding the World, her new book of travel essays now available at OR Books.

0 Comments