In New Orleans, we usually recoil at comparisons to Hurricane Katrina. Phrases like “Trump’s Katrina” round off the important edges of both our 2005 tragedy and the current one. Yet as I walk my newly quieted neighborhood in New Orleans these past few weeks, it is impossible not to recall—or flash back to might be a better phrase—the months after the 2005 levee breaks and subsequent flood, when these streets and lawns were covered by a gray ash, and loose power lines strung around like thrown spaghetti.

Then, as now, we’d know that friends were hurting, but we would not always be aware of the depth or character of their pain. In the weeks after the 2005 flood, we’d hug hard and ask, “How’s your house?” Now we call across the street, “Everyone OK?”

“Some people got lost in the flood; some people got away all right.” Randy Newman sang those lines in “Louisiana 1927,” his classic song about yet another hard time. Now, as then, we’re not sure who is going to fall in which category. But we can start to make some guesses. Those lost will often be those with less money and resources, or who are without homes, or who are imprisoned or undocumented. The workers who power our tourism-driven economy are especially vulnerable. And, as with Katrina, the pain is falling disproportionately on our African-American population.

Also like Katrina: The concerned phone calls and texts arrive nonstop, provoking both gratitude and emotional exhaustion. Presumably in the course of her work, my wife, a pediatrician, contracted Covid-19. She’s better now, though two-fifths of her senses—smell and taste—are still knocked out, and she misses them. Every day, the calls from our loved ones around the country: “How is she?” “Better.” “I’ve heard it’s bad down there?” “Yes, it is.” “What’s going to happen?” “I don’t know.”

Then there’s Mardi Gras. In New Orleans, our personal lives and public celebrations are inseparable. In fact, they’re joined at the heart. In 2006, the nation seemed perplexed that New Orleans, still a patchwork of FEMA trailers and broken homes covered in blue tarp, was going to nonetheless celebrate Mardi Gras. We did, and it was difficult and glorious. This year, we found ourselves embroiled in a different type of Mardi Gras controversy. Applying a selective historical amnesia—an amnesia that is likely to be stoked in months to come by bad-faith actors attempting to paper over the Trump administration’s grave mistakes—journalists and commentators from Jake Tapper to Meghan McCain grilled our governor and mayor on the decision to hold Mardi Gras. Such questions are blithe and disingenuous: There were simply no serious public discussions about canceling large public gatherings at the time.

To be sure, New Orleans is used to playing the scapegoat. For generations, people have arrived in our city to chase a skirt or a suit, and puke a hurricane into our gutters, then return home to say the devil made them do it. We are happy to play the devil as called upon: It’s a gig, after all. But this is a different type of scapegoating, and we will refuse, again and again, to take responsibility for a failure of the federal government. We will fight back, every time.

It’s also true, however, that many of the survival skills we learned during Katrina are proving to be of no use to us now. After the flood, my friend Chris Rose, then a columnist for The Times-Picayune, became a folk hero for his articulations of what makes us so different down here: “We dance even if there’s no radio. We drink at funerals. We talk too much and laugh too loud and live too large and, frankly, we’re suspicious of others who don’t.”

Those words struck a deep chord and can still be seen here on T-shirts and magnets. But not long ago, a local man who’d organized just that kind of jazz funeral was arrested for violating social distance orders. The tuba player in the band was issued a summons. For this disaster, we suddenly have to act less like ourselves and more like the rest of the country. There is no filling the streets when a jazz legend dies, mourning with the family until the body is cut loose, then celebrating our chance to live and laugh with songs like “Didn’t He Ramble.”

One of our most beloved jazz legends of all, Ellis Marsalis, died with symptoms of Covid-19. Of course we stayed home. We shared his music via the internet and our community radio station WWOZ-FM. We posted his sons’ reflections and our own stories instead of shouting them into each other’s ears over blasting trombones and trumpets. This is New Orleans now, as it must be.

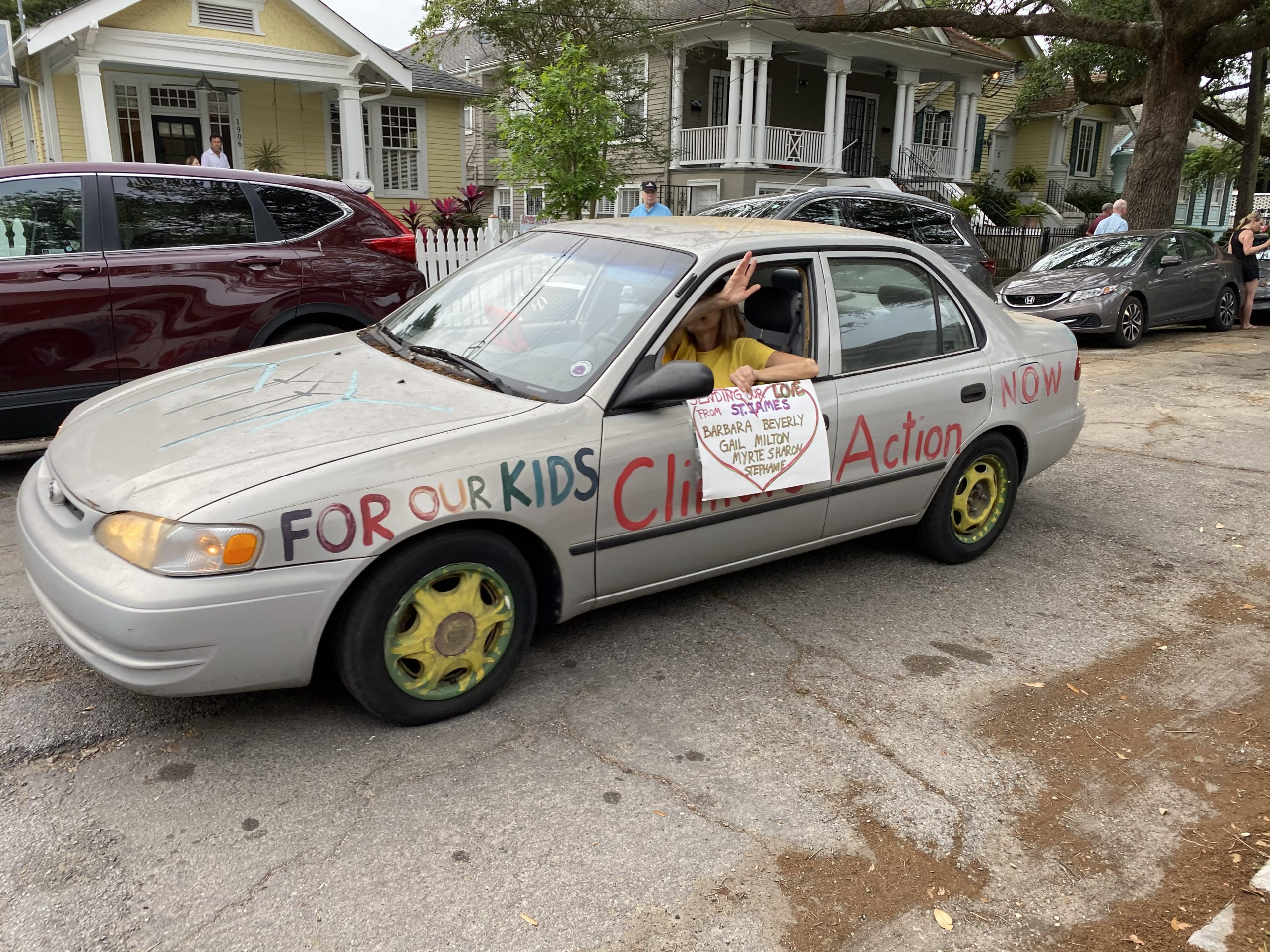

I also saw a promising side of my city in the early weeks of the pandemic, following another death presumably from Covid-19. This loss was even closer to me. Reverend William Barnwell was an Episcopalian minister and longtime social activist, and he lived a few doors down. His fellow minister, Reverend Gregory Manning, decided that he needed to help the community find a way to pay its respects to Barnwell’s widow and family. This is why, on a recent sunny afternoon, a line of cars processed up my street, waving signs and playing brass band music from speakers. Manning stood across the street from the Barnwell home, his unamplified yet booming voice leading a block of people, all carefully spaced apart, into the gospel song that has become a civil rights and resistance anthem, “Victory is Mine.”

After the last car had driven away, I caught up with Manning. “These are new times,” he said. “Sometimes that calls for new rituals.”

None of us will be the same after this, but we will go back to some old ways. I expect we’ll again meet on the streets, dancing together in the summer sweat, slapping the backs of friends, laughing with strangers. In the meantime, we’re trying out something new. Once again, New Orleans can show the world how we take care of our own, body and soul.

Michael Tisserand’s most recent book is Krazy: George Herriman, A Life in Black and White. He can be reached at MichaelTisserand.com.

0 Comments