Throughout the long struggle for African-American freedom, tactical and philosophical nonviolence was rarely predominant. The quest for full civil and human rights was long, arduous, and multifaceted. And, whether in the 1870s or 1970s, black activists and citizens proved willing to take up arms to defend against white supremacy’s architects and agents.

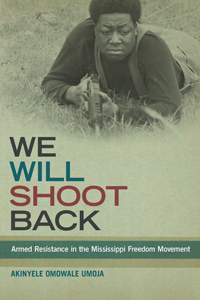

In his new book, We Will Shoot Back: Armed Resistance in the Mississippi Freedom Movement, historian-activist Akinyele Omowale Umoja works to trace this history. Heavily anchored in the 1960s and 1970s, Umoja examines the efforts of black people in towns and rural hamlets across Mississippi, as they sought to protect their lives, rights, and dignity against onslaughts of racial proscription and violence. He argues that we cannot fully understand the black freedom movement without appreciating the centrality of armed resistance in it.

| In We Will Shoot Back, Akinyele Omowale Umoja argues that we cannot fully understand the black freedom movement in Mississippi without appreciating the centrality of armed resistance in it. |

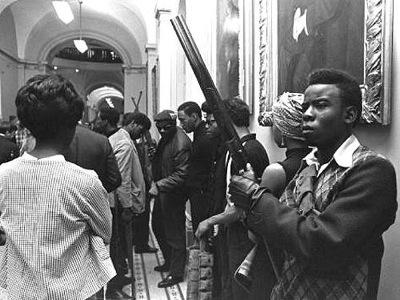

Working from a broad definition of armed resistance that “includes armed self-defense, retaliatory violence, spontaneous rebellion, guerilla warfare, armed vigilance/enforcement, and armed struggle,” Umoja demonstrates the ways strict nonviolence never ruled the day in Mississippi. The earliest chapters, stretching from Reconstruction through mid-20th century Mississippi, are too diffuse and scattered in their evidence to be effective. But when it turns to the 1960s and 1970s, We Will Shoot Back offers a compelling portrait of a southern black resistance culture wherein a willingness to use armed resistance was the stuff of necessity.

Contrary to popular and academic depictions wherein the morally principled civil rights movement descended into the ignoble violence of Black Power, nonviolence was the foreign concept in the minds of many southern blacks. As movement activist Rudy Lombard described it, local people defended themselves as an obvious matter of course; self-defense was simply “a part of the way they normally lived.” These weren’t retributionists, but people for whom experience and common sense dictated that when a white racist leveled a gun at you, you pointed one back.

Umoja is especially good at showing how armed self-defense was woven into the fabric of a movement that is normally characterized as nonviolent. For instance, fieldworkers with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Conference on Racial Equality—two organizations avowedly nonviolent in their origins—knew from personal experience that armed self-defense worked. Local blacks frequently housed SNCC and CORE activists, and in so doing protected them from white supremacists with both show of arms and gunfire. These practitioners and proponents of nonviolence, in other words, depended upon the willingness of others to take up arms in their defense.

Yet questions remain about whether Umoja stretches his argument too far. There are times where it seems that he would consider anything that wasn’t explicitly nonviolent to be “armed resistance,” which has the effect of rendering the term amorphous and diminishing its utility. After all, as Umoja notes, the most common tool used by Mississippi freedom activists after 1964 and onward through the 1970s was consumer boycotts of white businesses. Such boycotts were often enforced by violence or the threat thereof, but armed resistance (as most people would consider it) was hardly their constitutive feature. The book, then, would perhaps be more effectively framed not as a study of “armed resistance,” but rather as one of the practical interplay of nonviolence and self-defense.

Yet questions remain about whether Umoja stretches his argument too far. There are times where it seems that he would consider anything that wasn’t explicitly nonviolent to be “armed resistance,” which has the effect of rendering the term amorphous and diminishing its utility. After all, as Umoja notes, the most common tool used by Mississippi freedom activists after 1964 and onward through the 1970s was consumer boycotts of white businesses. Such boycotts were often enforced by violence or the threat thereof, but armed resistance (as most people would consider it) was hardly their constitutive feature. The book, then, would perhaps be more effectively framed not as a study of “armed resistance,” but rather as one of the practical interplay of nonviolence and self-defense.

There are other issues. One is the probably unsustainable suggestion that these 20th-century practices of armed resistance might represent an African-American retention of African military and cultural traditions. Another is Umoja’s distracting use of the folkloric “Bad Negro” and “trickster” tropes to describe Freedom Movement activists.

In short, We Will Shoot Back is uneven. Though nominally about armed resistance, there are too many moments where it’s difficult to accept that what’s being discussed is “armed resistance” rather than simply not nonviolence. All the same, it offers important contributions for expanding our understandings of the freedom movement’s risks, goals, and ideologies. By focusing on the experiences and tactics of local Mississippians for whom dogmatic nonviolence made no sense, Umoja forces readers to reconsider the strategies and stakes in the struggle for black freedom rights in this country.

Simon Balto is a Ph.D. candidate in history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

0 Comments