What is a police state, and have we become one? These questions are asked with higher frequency since young Edward Snowden blew a loud whistle on our government spying on our phone calls and e-mail. But there has long been a more prosaic, everyday quality to American over-policing that doesn’t require high-tech surveillance. The over-criminalization of daily life in the U.S. includes outsourcing school discipline to police departments, the use of cops and prosecutors to regulate our financial system, and then of course there’s the TSA, now expanding its duties beyond airport security. Even our prisons are over-policed, with 80,000 Americans warehoused in long-term solitary confinement. To be fair, there are areas where we are quite far from the old East German police state—our per capita current incarceration rate, for instance, is more than three times higher than in the defunct German Democratic Republic.

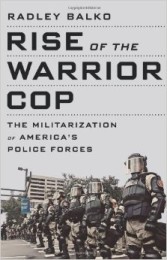

Radley Balko is the premier journalist on the police-brutality beat, and his new book, Rise of the Warrior Cop, is an artfully arranged collection of his recent work charting the militarization of America’s police forces mostly as part of our “war on drugs.” Which is anything but a metaphor. In fact the w-word is a literal description of the expensive, violent and failed campaign against narcotics. The war continues, with police departments buying up more and more second-hand military gear, recruiting directly from recently returned veterans, and indulging ever more in an us-versus-them counterinsurgency tactics.

The concepts of war and policing have blurred, both in the media and inside police departments. Former Los Angeles police chief Daryl Gates, for example, likened his city’s 1991 riots to World War II. And since 9/11 there has been a deep (and for police force budgets, lucrative) confusion between local law enforcement and “counterterrorism.” James Forman Jr. of Yale Law School has argued, convincingly, that the Bush-Obama War on Terror is our War on Crimes/Drugs exported to more exotic locales.

The concepts of war and policing have blurred, both in the media and inside police departments. Former Los Angeles police chief Daryl Gates, for example, likened his city’s 1991 riots to World War II. And since 9/11 there has been a deep (and for police force budgets, lucrative) confusion between local law enforcement and “counterterrorism.” James Forman Jr. of Yale Law School has argued, convincingly, that the Bush-Obama War on Terror is our War on Crimes/Drugs exported to more exotic locales.

Balko efficiently sketches how over the past half-century Supreme Court jurisprudence and police practices such as the use of SWAT teams and no-knock raids have disemboweled Fourth Amendment protections against illegal search and seizure. Today SWAT teams, heavily armed with flash-bang grenades, Tasers, tanks and high-caliber weapons, are deployed for routine police functions, resulting in a lot of innocent people getting shot dead along with their family dogs.

How is this tolerated? To Republicans, official violence appears to be delight in itself. For Democrats, the pathological need to prove that they are not sissies has led to no end of misery, from Mayor Wilson Goode’s firebombing of Philadelphia row houses to Bill Clinton’s prison expansion, to Barack Obama’s crackdown on medical marijuana dispensaries.

Balko offers some solutions—greater transparency, accountability, etc.—without a lot of thinking about U.S. history, race or class. But analytical shallowness is no defect in a book of such breadth and clarity.

The politics of reining in militarized policing makes for strange bedmates, with the compass points of left and right frequently sent spinning.

Balko also explores the one of the big institutional incentives sustaining militarized over-policing: asset-forfeiture laws that allow police departments to seize the wealth and possessions of people only marginally involved in the drug trade then convert the plunder into big departmental budgets, a revenue model that makes such predatory behavior recession-proof.

Balko finds solutions in police chiefs who have rejected militarization, like Jerry Wilson, the Nixon-era chief of Washington D.C. police; Joseph McNamara, a Hoover Institution fellow and former police chief in Kansas City and San Jose; Norm Stamper, former police chief of Seattle whose Zen wisdom is found throughout Balko’s book. All three kept crime down while generally treating people like citizens.

The politics of reining in militarized policing makes for strange bedmates, with the compass points of left and right frequently sent spinning. Balko himself is a conservative libertarian and Second Amendment true believer. He even enthuses over “the symbolic Third Amendment” prohibiting forced quartering of soldiers. And the young journalist has already snorted up great mounds of Koch brothers funding.

This is no reason not to read Balko’s fine exposé, to be placed on the bookshelf right next to Michelle Alexander’s important 2010 study The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, which approaches the same issues from a radically different and complementary perspective.

Chase Madar is an attorney in New York, and the author of The Passion of Bradley Manning: The Story behind the Wikileaks Whistleblower (Verso).

0 Comments