Fifty years ago, a Johns Hopkins–educated zoologist did something that few at the time thought was possible. With the publication of one book, she started a national debate about the universally accepted use of synthetic pesticides, the irresponsibility of science, and the limits of technological promise. She also challenged the metastatic growth of the synthetic chemicals industry that grew out of World War II.

Silent Spring was Rachel Carson’s third book, following The Sea Around Us and The Edge of the Sea. The Sea Around Us had won the 1952 National Book Award for nonfiction and remained on the New York Times bestseller list for 21 months. Yet it is unlikely that Carson, who had spent most of her career as an editor for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, had any idea of what the publication of Silent Spring would engender.

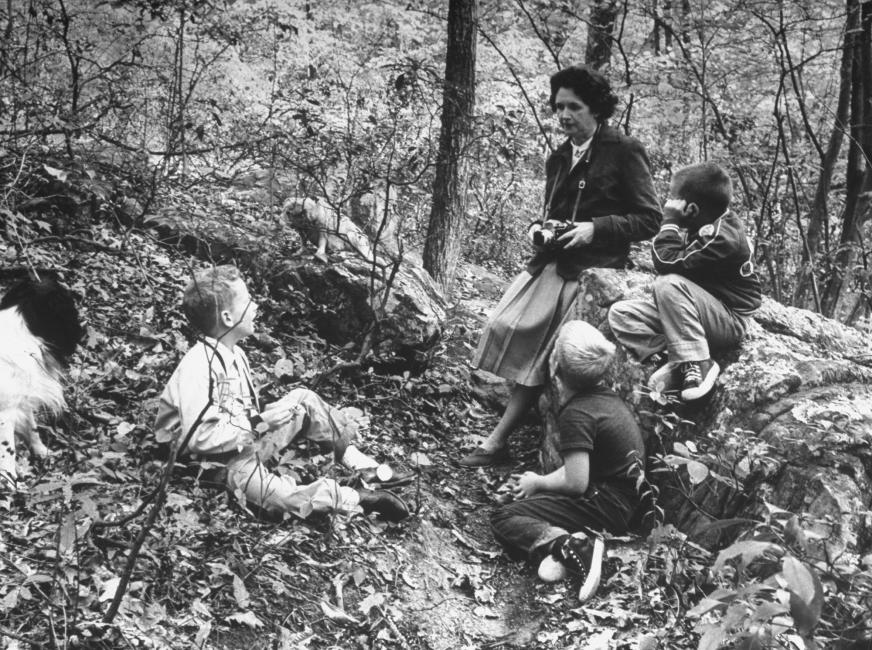

Carson became interested in the harmful effects of pesticides, especially DDT, in the late 1950s. DDT was first commercially produced just prior to World War II, and was used to reduce the threats posed by insects to U.S. troops overseas. After the war, DDT was promoted as a great scientific advance and was widely and successfully used as an insect killer in the United States. The chemical was considered to be so benign that parents casually watched their children running in billowing white DDT clouds sprayed from trucks in residential neighborhoods.

Carson’s research focused on organic pesticides like chlordane, heptachlor, and aldrin, as well as DDT. She documented the widespread death of birds that had been exposed to the chemicals, as well as reproductive, birth, and developmental abnormalities in mammals. All life, she wrote, is a “chemical factory” dependent upon oxygen to power the cell machinery. Citing the work of Nobel scientist Otto Warburg, she explained in clear terms why repeated small exposures to pesticides and nuclear radiation change the ability of the cell to carry out normal activities, resulting in malignancy or defective offspring—the reason there is no “safe” dose of a carcinogen. Many scientific experts shared her concerns.

The New Yorker ran three excerpts of Silent Spring in June 1962, before the official September 27 publication date. The response was swift and resounding. CBS began preparing a nationally broadcast special on the book. Page one of the July 22 New York Times featured a story entitled “Silent Spring Is Now a Noisy Summer.” On August 29, a reporter attending President Kennedy’s press conference asked if the federal government was examining the growing concern about DDT and other pesticides. Kennedy responded: “Yes…I think particularly, of course, since Miss Carson’s book.” A month before the publication date, Houghton Mifflin had advance orders for 40,000 copies and had a 150,000-copy contract with the Book-of-the-Month Club.

The chemical industry didn’t wait to read the book. Carson’s short but devastating treatise was a threat to their bottom line, and the industry that manufactured DDT and other pesticides Carson had described reacted angrily to her scientifically sound arguments that their products were harmful. They attacked Carson’s expertise. They attacked her methods. They attacked her motivations. They attacked her conclusions. They threatened to sue Houghton Mifflin and The New Yorker.

In a relentless campaign to destroy her character, the industry distributed pamphlets, published articles, and vilified Carson in media interviews. They described her as “fanatic” and “hysterical,” yet almost all international scientists agreed with Carson. A Scientific Advisory Committee assembled by Kennedy issued a supportive report in May 1963. In response to the shrill attacks of her industry critics, Carson calmly stuck to the facts. She died at age 56 from breast cancer, 18 months after Silent Spring was published.

Many regard Carson as the founder of the American environmental movement. Yet the movement had already begun. Albert Schweitzer, well-known scientists such as Linus Pauling, pediatrician Benjamin Spock, and Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas had already been speaking out against the dangers of above-ground atom-bomb testing. Citizen groups like Women Strike for Peace organized increasingly large demonstrations against such tests.

But to a large extent, Silent Spring sparked the movement that endures today. In 1967, scientists and activists founded the Environmental Defense Fund. On April 29, 1970, one week after widespread demonstrations on the first Earth Day, President Nixon’s Advisory Council on Executive Action proposed the Environmental Protection Agency, which became a reality later that year. And in June 1972, after three years of federal hearings and scientific inquiries into the question Carson raised in Silent Spring, EPA Director William Ruckelshaus issued an order that banned the use of DDT in the United States. The environmental movement was in full swing.

Despite the efforts of Carson and others who followed, a long list of chemicals is still in daily use—arguably more than ever. It includes pesticides, herbicides, industrial agents, fuels, preservatives, food additives, dyes, household products, medicines, and more.

The benefits of chemicals must always be weighed against their risks—but those risks must be objectively calculated. As Carson wrote in Silent Spring:

The most alarming of all man’s assaults upon the environment is the contamination of air, earth, rivers, and sea with dangerous and even lethal materials. This pollution is for the most part irrecoverable: the chain of evil it initiates not only in the world that must support life but also in living tissues is for the most part irreversible. In this now universal contamination of the environment, chemicals are the sinister and little-recognized partners of radiation in changing the very nature of the world—the very nature of its life.

Fifty years after the publication of the book, the corporations that produce and market the chemicals are far larger. Their lobbyists and PR machines are more well-funded and sophisticated and exert unprecedented influence over regulators, the media, and, most critically, elected officials.

A Congressional resolution introduced by Maryland Democratic Senators Ben Cardin and Barbara Mikulski, honoring Carson on what would have been her 100th birthday in 2007, was blocked by Senator Tom Coburn (R-OK), who complemented his vote with disparaging remarks about the author. “Millions of people in the developing world, particularly children under 5, died because governments bought into Carson’s junk-science claims about DDT,” he said in response to the resolution.

Today, the industry and its trade associations echo Coburn’s remarks and depict Carson as the leader of a mass-murder campaign that today allows diseases such as malaria to proliferate because there is no chemical check on mosquitoes. In 2009, Todd Seavey of the industry-backed American Council on Science and Health wrote on World Malaria Day: “We need DDT Day…. Anti-chemical greens (inspired by Rachel Carson’s fear-mongering book Silent Spring) may already be humanity’s most prolific killers.”

The EPA never banned DDT for use against malaria, and Carson herself never supported a universal ban on pesticides. Instead, she wrote, “Practical advice should be ‘Spray as little as you possibly can’ rather than ‘Spray to the limit of your capacity.’”

Man-made chemicals will always be a part of life on earth. The volume of chemicals is massive, and the slow decay of many means they will be part of the biosphere for decades and centuries. The legacy of Silent Spring is that much can and should be done to reduce the health risks they pose, without sacrificing progress. About 41 percent of Americans will develop cancer. The current generation of children, compared to their parents or grandparents, has higher rates of disorders including low weight births, cancer, asthma, diabetes, autism, and ADHD. While multiple factors influence disease risk, exposure to toxic chemicals is one factor.

We have ignored Carson’s findings to our peril.

Joseph J. Mangano is Executive Director of the Radiation and Public Health Project and author of Mad Science: The Nuclear Power Experiment (O/R Books). Janette D. Sherman is an internist and toxicologist and a contributing editor of Chernobyl: Consequences of the Catastrophe for People and the Environment (New York Academy of Medicine). Visit www.radiation.org and www.janettesherman.com.

0 Comments