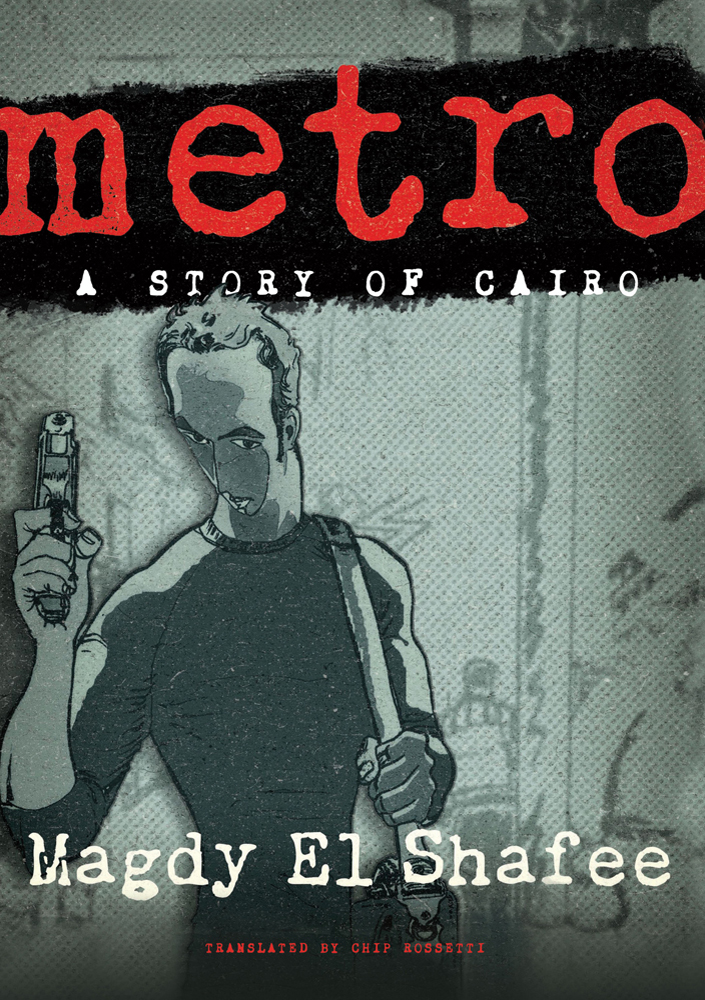

Reviewed: Metro: A Story of Cairo by Magdy El Shafee (Metropolitan Books, 112 pp., $20). Magdy El Shafee is a Libyan-born Egyptian comics artist. In 2008, his first graphic novel, Metro: A Story of Cairo, was published in Egypt.

Reviewed: Metro: A Story of Cairo by Magdy El Shafee (Metropolitan Books, 112 pp., $20). Magdy El Shafee is a Libyan-born Egyptian comics artist. In 2008, his first graphic novel, Metro: A Story of Cairo, was published in Egypt.

It recounts the fictional adventures of a down-on-his-luck, quasi-superheroic software designer who angrily roams the streets and subway (the Metro) of Cairo. The book was banned in Egypt upon its publication, and the author and publisher were tried and fined for offending “public morals.” Apart from a brief scene of nudity and sex, what was likely deemed “offensive” was political: Metro’s depictions of economic and political corruption and violent demonstrations constitute literary protest and anticipate the popular frustrations and some events of the Arab Spring. Though Metro remains unavailable in Egypt, it now appears in an English translation by Chip Rossetti.

The plot is an uneven potboiler interspersed with haunting moments. The young, clever, and unemployed Shehab and his friend Mustafa are indebted to a group of thugs. At their wits’ end, they rob a bank, beating up fat cats in the process and delivering one man to a violent mob in the name of economic justice. Predators stalk Shehab’s girlfriend, Dina, a journalist in Western garb who attends antigovernment demonstrations, but he chases them off with a stick and Spidey-style leaps. He witnesses a murder. He beats up hired bullies at a demonstration, including Mustafa’s corrupt brother. He discovers a conspiracy that implicates Egypt’s powerful upper echelon. The art, though not without skill, is rough, busy, and inconsistent, as if the artist is still searching for a signature style. The best panels in the book are a series of stylized cartoons illustrating a morality tale told by a destitute old man.

Though Metro will likely resonate with young Egyptians should they ever get to read it, for Western readers, the book’s storyline and art are perhaps less important than the window it offers onto Arab culture and Egyptian political ferment. There are subway lines much like Europe’s or New York’s; women in head scarves, tight clothing or both; “hicks” from southern Egypt in long shirtlike garments; ringtones (and funny lyrics) from popular Egyptian movies; angry youth glued to cell phones. What are they angry about? The lack of jobs, even for tech-savvy types. The sense that the government is lying, and that the rich are victimizing the poor, including the elderly. The knowledge that it would be foolish to trust the police or the media, even—or especially—as a murder witness. “I can’t remember when I became so angry,” Shehab muses in the book’s opening panels as he contemplates his bank heist. “All I had on my side was my brain.”

A particularly depressing revelation comes as Mustafa’s brother explains how he made money by attacking protesters at a demonstration: “How’d it look if the police were beating people up? There were photographers and stuff. But we can get in there and beat them up, and then it’s just ordinary guys having a fight. And that’s when the police step in…and take their sweet time breaking it up.”

Especially in the wake of the Arab Spring, the novel is most moving when it expresses despair about Egyptian society. “We’re all living in one big cage…hoping maybe someone will throw us a bit of cheese,” says Shehab. “I have to get out of this whole lousy cage.” Of course, the events in Tahrir Square represent a mass attempt to do just that. And Metro’s societal woes blurrily mirror our own: Bankers take advantage of the little guy. The poor get handouts on religious holidays (faith-based charity, anyone?). Skilled workers remain jobless. Sexual violence dogs women (again, El Shafee is eerily prescient, viz. Lara Logan). And political apathy is deadly in any country: “People are numb,” Shehab remarks. “They put up with so much, they just say ‘Well, that’s how things are in this country of ours.’ ” Reading Metro suggests that the difference between Egyptians’ frustrations and our own may be, in large part, a matter of degree.

Jenny Blair is a writer, editor, and M.D. Her website is www.jennyblair.com.

0 Comments