(Source: Mashable)

It makes sense that we are indignant (though perhaps not indignant enough) about the scandal of illicit spying by America’s National Security Agency. But we should not be surprised. We should have seen this coming. Our reaction recalls Nietzsche’s reproach of people who spend their lives being surprised to discover things they had already hidden from themselves.

Our uncertainty comes from the ongoing hungover of those debauched years in which we celebrated the liberating promise of the internet. Some were pleased that anyone could express any opinion without the permission of newspaper editors; others that books could be published without the license of a publishing firm; still others that citizens were on the verge of doing away with political parties, institutions, and their representatives. And there were those who celebrated the death of all state secrets and the coming of Total Transparency.

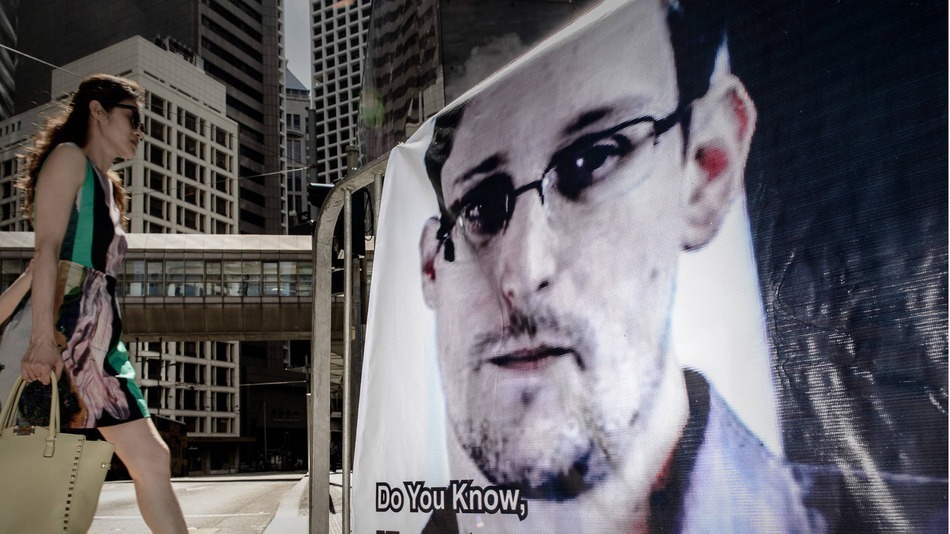

| Edward Snowden revealed a state of affairs we helped create. We can observe because we let ourselves be observed. The more we know about the World Wide Web, the more the World Wide Web knows about us. |

Knowledge would be universally available and everything could be shared. Informing ourselves about the weather, connecting to social networks, buying products online, sending instant messages—all of these, we told ourselves, represented a great leap forward. We believed we would all be watching from now on: critical observers who were not themselves observed.

It should now be clear that Edward Snowden revealed a state of affairs we helped create. The internet is a hub of self-exhibition, even for the most discreet. Existing on the internet means revealing oneself through data, itineraries, relationships, and decisions. Moving about the web, taking advantage of its virtualities, is itself the establishment of two-way relationships. We can observe because we let ourselves be observed in an immense surveillance machine. The more we know about the World Wide Web, the more the World Wide Web knows about us.

We accept this implicit digital contract. We feed the web every day and every day we leave a trace. Nothing becomes lost or faded with time. Google searches are recorded; Facebook interactions are saved. Web usage implies a giant data exchange. Even spies leave traces and people like Edward Snowden track them to challenge or obstruct their spying.

For this reason, one could argue that Snowden and Chelsea (née Bradley) Manning represent the self-regulatory capacity of democracy, the only political system in which the work of secret services come to light and the messenger survives. Is that possible in Russia or China?

In the face of those who have exaggerated its democratizing possibilities, we now know that the internet is more like a bazaar than a gathering place. Our opinions, likes and dislikes, desires, and locations are complied by companies that take this data as their own private property. By feeding their databases, consumers increase the value of companies that afford consumers what (they believe) they need. The web’s anarchic-liberal ideological feel gives the impression that we in charge, that we are being served, and that only our needs are being meet.

Snowden has shown us the truth: the web serves us but it also manages us in accordance to political objectives. That is why it is no coincidence that the great internet companies and governments are collaborating, on the one hand, because of the potential profit that this data represents and, on the other, in the name of security or geostrategic interests.

We are most likely entering a second internet era in which some naiveté will disappear and certain risks are addressed. Conflicts between freedom and control, government and citizens, providers and users, transparency and data protection will become acute. We will need to respond. We will need to regulate phenomena such as “the right to be forgotten,” privacy and the willingness to reveal data. New procedures for protection and encoding will surely be invented, as will new legal regulations and new forms of diplomacy and cooperation.

Spying will not disappear, but it will have to be more respectful of legal questions and more intelligent. Secret services have long recognized the need for better filters.

Trust is the best filter. President Obama could find out more by calling German Chancellor Angela Merkel than by bugging her phone and thus destroying trust between them. Building trust is our great challenge, including and principally in regards to security measures.

Daniel Innerarity is a professor of political philosophy at the University of the Basque Country in Spain. He is currently a visiting professor at the London School of Economics. His latest book is The Future and Its Enemies: In Defense of Political Hope. This article was translated by Sandra Kingery.

0 Comments