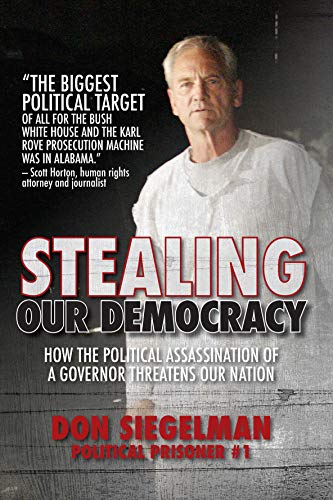

On June 28, 2007, Don Siegelman made his final appearance in U.S. District Court Judge Mark Everett Fuller’s courtroom. The former secretary of state, attorney general, lieutenant governor, and governor of Alabama was in leg-irons, handcuffs, and a jailhouse jumpsuit, as directed by the judge. Appointed to the bench by George W. Bush (then resigning after he was caught brutally beating his second wife, Kelly Fuller, in an Atlanta hotel room), Fuller was closing out the trial that ended the career of the last Democratic governor in the South.

If I didn’t know the story, which I followed for two years in this publication, I might have considered the title of Siegelman’s new book—Stealing Our Democracy—broad and overstated for a first-person account of one man’s prosecution by his political adversaries. Which it is not. The story the deposed Democratic governor tells begins in Montgomery. But the quiet machinations behind the political hit job that put him away for five years played out on the fifth floor of the Justice Department and in the Bush White House, where Attorney General Alberto Gonzales and senior adviser to the president Karl Rove were purging U.S. attorneys and replacing them with partisan loyalists. And where, according to sworn testimony, emails, and internal documents Siegelman obtained, Rove was quietly promoting his prosecution.

Stealing Our Democracy is more than one take on the partisan abuse of the office of attorney general, which began with John Mitchell, was continued by Ed Meese and the hapless Gonzales, and today is unabashedly and openly practiced by Bill Barr. By taking into account the secondary players—Jeff Sessions receiving illegal campaign contributions, Jack Abramoff defrauding Indian tribes and collaborating with evangelical hustler Ralph Reed to funnel millions stolen from Indian casinos into Alabama politics—Siegelman has told a much larger story, and has given us an indispensable primer on the squalid, systemic partisan corruption that metastasized into what today is the party of Donald Trump.

The antagonists aligned against Siegelman as he took the oath of office in 1998 made any wager on the end of his career a safe bet:

Karl Rove, the strategist and political operative who made George W. Bush a governor and a president and along the way had worked with a rogue FBI agent investigating every statewide Democratic officeholder in Texas.

Billy Canary, a legendary Alabama-based political consultant who had worked with Rove on the Bush-Quayle campaign.

Leura G. Canary, vetted by Rove and appointed by Bush as a U.S. attorney in Alabama.

Alice Martin, vetted by Rove and appointed to serve as a U.S. attorney in Alabama.

The two women were known as Canary’s “girls.” According to a sworn affidavit submitted during the Siegelman prosecution, Bill Canary was overheard on the phone telling the son of Bob Riley, Siegelman’s Republican rival, “not to worry, that he had already gotten it worked out with Karl and Karl had spoken with the Department of Justice and the Department of Justice was already pursuing Don Siegelman.” Bill Canary reassured Riley, according to the testimony, that “his girls would take care of” Siegelman: Canary was referring to his wife, Leura, the United States attorney in Montgomery, and Alice Martin, her counterpart in Birmingham.

Judge Mark Everett Fuller, who (a) while presiding over Siegelman’s criminal trial held controlling interest in a company attempting to renew a $175 million annual contract with the Defense Department, (b) could not have forgotten that in 2002 an investigation overseen by Siegelman had revealed that while serving as district attorney the judge had improperly doubled the salary of his chief investigator, costing the state retirement system $300,000, and who (c) eventually resigned from his lifetime appointment to the federal bench under a cloud of multiple charges of ethical violations including judicial misconduct, misdemeanor battery, perjury, and conflicts of interest.

Bill Pryor, chief judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit, a Karl Rove client who had served as first assistant to Alabama Attorney General Jeff Sessions, was himself elected attorney general in 1998, and today is on Donald Trump’s short list for the Supreme Court.

To the crime syndicate known as the Alabama Republican Party, Siegelman posed a challenge.

As a “New South Democrat,” he had been elected secretary of state in 1978, attorney general in 1986, and lieutenant governor in 1994, and in 1998 he defeated incumbent Republican Governor Fob James, winning 58 percent of the vote and a majority of both white and black voters.

Don Siegelman, it appeared, was impossible to defeat at the polls.

So his adversaries got creative.

Two months after Bill Pryor took the oath of office as Alabama’s attorney general in 1998, he issued a subpoena for the Democratic governor’s campaign finance records.

“I knew an investigation by Karl Rove’s client was underway,” Siegelman writes in Stealing Your Democracy.

As a reporter who wrote a book about Rove’s scorched-earth ascent to power in Texas, I was familiar with the deployment of FBI agents looking for low-hanging fruit in offices of Democratic officeholders. In Alabama, investigations were not encumbered by the institutional constraints under which active-duty federal agents worked. They were conducted by a team of ex-FBI agents initially recruited by Jeff Sessions when he was state attorney general. And they went after Don Siegelman.

In 2002, Siegelman was indicted and prosecuted by assistant U.S. attorneys working in Leura Canary’s office. Federal District Judge U.W. Clemon dismissed the case on the first day of testimony, later saying: “In my 30 years on the federal bench, I’ve never seen a federal prosecution with such a glaring lack of substantial justification.”

The clean bill of health from a federal judge was helpful, but the fraud indictment was fodder for the campaign of Republican Congressman Bob Riley, who was trying to unseat Siegelman in 2002. Riley, another Rove client, rode a wave of dark money provided by lobbyist “Casino Jack” Abramoff and Christian Coalition founder Ralph Reed, the schemers behind campaigns by the Christian Coalition of Alabama and “Citizens Against Legalized Lottery.” In 2006, Abramoff, at the time a high-dollar patron of then-House Majority Leader Tom DeLay, pleaded guilty to conspiracy, fraud, and tax evasion after defrauding Indian tribes of $24 million. Ten years after leaving prison as a remorseful penitent, Abramoff recently pleaded guilty to federal charges of conspiracy for failure to register as a lobbyist.

When Siegelman was declared the winner on election night, Riley refused to concede, insisting that results from one county had not been counted. Those results had Siegelman up by a slim margin—until 4 a.m. the following day, when a “computer glitch” in one voting district put his Republican challenger ahead by 3,000 votes. While Siegelman filed for a recount of paper ballots from the county in question, Attorney General Pryor certified the vote, which under Alabama election law precludes a recount.

Siegelman conceded, began laying the groundwork for a 2006 campaign, and was indicted yet again.

The fact situation in the case that sent Don Siegelman to prison for five years was simple. As governor, he formed a PAC to support an initiative to establish a state lottery that would have provided free college for Alabama high school graduates. Then he persuaded health care CEO Richard Scrushy to contribute $500,000 to the fund and accept an appointment to a state board, the same board on which Scrushy had previously served under a Republican governor.

The law governing the case was not so simple. U.S. Attorney Canary framed the transaction as a bribe, though neither Siegelman nor his campaign received any of the money. (After Canary recused herself, emails obtained by Siegelman established that she remained involved in the prosecution.)

At the end of a two-month trial, Fuller instructed the jury that an “implied” quid pro quo rather than an “express” or “explicitly asserted” offer of a favor in exchange for a contribution would be enough to establish guilt.

With the jury deadlocked on the eve of July 4, Fuller warned: “Look, I’ve been appointed for life. I can keep you here until next July if I want to. Bring me a verdict of a partial verdict.”

The jurors relented, and Don Siegelman became the first public official ever convicted under the “Honest Services Fraud” contract. Fuller tripled the term recommended in sentencing guidelines, ordering Siegelman to serve 88 months.

He would serve five years, first in Oklahoma City, 850 miles from his home, then in Oakdale, Louisiana, 459 miles from Montgomery. Fuller could have had him incarcerated in Pensacola, a two-hour drive from his family in Alabama.

More than 140 state attorneys general signed amici briefs filed in Siegelman’s appeal, and 113 petitioned Barack Obama to pardon him.

Siegelman was released from prison on February 8, 2017, three weeks before Barack Obama departed the White House. After spending more than $1.5 million on attorneys, and lacking a retirement fund, he’s reduced to living on Social Security.

Karl Rove’s net worth is $10 million. He’s an informal adviser to the Trump reelection campaign.

Lou Dubose is the former editor of The Washington Spectator.

0 Comments