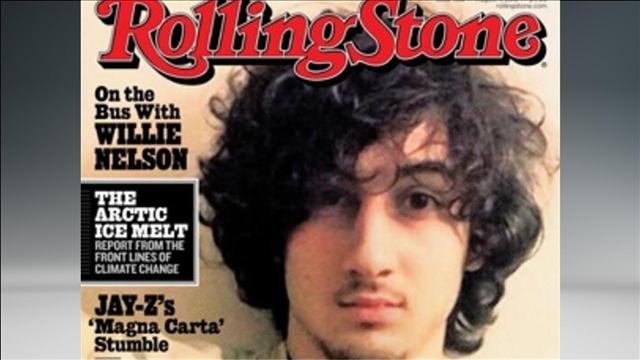

Despite the cries of protest and the outrage, and despite the widespread banning of the magazine, the image of Boston marathon bomber Dzhoktar Tsarnaev now depicted on the latest issue of Rolling Stone does not “glorify” the photogenic bomber.

Rather, the power of the image of Tsarnaev—wearing a designer t-shirt and looking every bit like a young hipster—is that it speaks directly to the discomforting cultural politics of the American terror experience.

Critics of the image have doubled-down on easy indignation about the political culture of terror—and demand a censorious uniformity from the media: Highlight the evil and downplay the humanity, otherwise you are making a celebrity out of a monster.

| The power of the photograph of the Boston Bomber lies in the way it intimates America’s unfolding and deeply complicated relationship with the terror in its midst. |

The critics fail to appreciate the distinction between the slippery cultural politics of terror and the starkly intolerant political culture that has emerged in the terror era. In doing so, they are playing right into the hands of American Islamophobes.

Erring on the side of the outrage, multiple retailers of the hoary rock & roll and politics magazine, some of them Boston-based, announced that they won’t make the issue available to consumers.

It’s easy to hit the boycott button and declare entitled provincial outrage over the perceived exploitation of the marathon victims.

But the tyranny of the outraged is winning out over the complexity of the bomber’s story, a complexity pungently reflected in the photo itself. Its power lies in the way the photo intimates America’s unfolding and deeply complicated relationship with the terror in its midst.

By way of comparison, in the aftermath of 9/11, photos of terrorist Mohammed Atta were widely used in magazines and newspapers, and no similar outrage or calls for a boycott ensued.

Why? Atta fit the description of the acceptable terrorist: He was a hateful-looking horror of a human being, and the image of him conformed exactly to the stereotype many American had, and wanted to indulge, about terrorists.

Tsarnaev looks like he just came from a rehearsal with a Strokes tribute band, and his appearance of calm, hip assimilation into the American cultural fabric is totally at odds with his despicable activities in Boston in April.

That disconnect is exactly what Rolling Stone contributing editor Janet Reitman was trying to explore in her piece.

Good luck finding a copy.

This obsession with image and the acceptable use of “controversial” photographs has a particular cultural context in a “socially mediated” America in which, after the Boston bombing, people obsessively scanned their cameras and iPhones to see if they’d captured a shot of Tsarnaev—as if capturing him digitally was in some way akin to actually capturing him.

Now many of those same people are saying, per the Rolling Stone cover: “Why do I have to look at this? Make it go away.”

Rolling Stone is faced with extraordinary backlash that claims the photo made a “rock star” and celebrity out of Tsarnaev by putting him on their cover. But he already was an anti-celebrity, and the magazine has put other monsters on its cover before, including and especially Charles Manson (who actually was a musician).

The “rock star” canard has become a generally accepted media-code signifier for a certain level of celebrity achieved. The Rolling Stone image blurred a distinction that had already been demolished by a media cognoscenti in dire need of a new cliché, and in doing so, ramped the discomfort level for the viewer—if only the viewer could see past the plight of the victims and appreciate the nuance of the image.

The “rock star” argument also dodges the cultural prejudice about terrorists that allows for certain photographic images, but not others. It didn’t matter that the magazine made obligatory reference to the bomber’s decline from human to monster on the cover. It only mattered that he looked like too much of a human.

Left with an image that didn’t hew to the accepted imagistic arc of the “typical” terrorist, the legion of outrage declared the photo was simply “in bad taste.”

“Write your article, Rolling Stone,” they said, “but don’t rub our faces in it.”

The same argument that now comes from Boston, purported bastion of liberalism and tolerance, was deployed by rank Islamophobes over a planned mosque and community center in the near-distant shadow of Ground Zero.

Left with cans of empty rhetoric when it came to the basic American ideal of religious tolerance, the Islamophobes retreated to the convenient facility of “bad taste.”

“Build your mosque,” they declared, “but don’t rub our faces in it.”

Tom Gogola won the Hillman Foundation Sidney Award in 2011 for a report in New York detailing waste in commercial fishing. Mostly recently he won the Press Club of New Orleans’ 2013 Investigative Reporting Award for work as criminal justice reporter for The Lens. His writing has appeared in Newsday and The Nation.

0 Comments