It’s London at the end of the 21st century. Still in the early stages of reconstruction in the wake of a global holocaust, the once great city lies in ruins but is cloaked in an augmented reality that makes it look exactly as it did before the world collapsed in a decades-long storm of environmental devastation, nuclear war, and serial pandemics. The rebuild is in the hands of a super-elite class of “curators,” who describe London not as a city so much as a kind of “incremental sculpture.”

This postapocalyptic vision is based on William Gibson’s novel The Peripheral, a dystopian narrative that boomerangs back and forth between the years 2032 and 2099, points in time that bookend a series of catastrophes called “The Jackpot,” so named because everything that could possibly go wrong on the planet does, erasing 90 percent of the human race.

Now set the wayback machine for 15th-century Florence. Filippo Brunelleschi designs, engineers, and builds the largest dome since Roman times for the Florence cathedral (the Duomo). Michelangelo carves David, the century’s most iconic sculpture. Leonardo creates the Mona Lisa, the world’s most famous painting. And presiding over what was one of the most intense bursts of creativity and ingenuity in Western history is the Medici family, owners of the largest bank in Europe for almost a hundred years.

Which world would you rather live in?

This is, in a sense, the key question underlying The Nexus. Will we succumb to existential collapse brought on by unchecked expansion, rapacious exploitation, and the sheer complexity of the problems we face, or can we use whatever intelligence and creativity we have left to prevent the end of the world as we know it?

A collaboration between Julio Mario Ottino, dean of the McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science at Northwestern University, and Bruce Mau, multidisciplinary designer, educator, and artist, this book bets large on the latter. Its core thesis—as expressed in bold type and breathless prose across a two-page spread early in the book—is that because the world “faces enormous challenges of unprecedented complexity—problems that intertwine in a dizzyingly interconnected, interdependent and changing landscape,” we must “adopt new ways of thinking and working that cross the boundaries of classical knowledge . . . at the nexus where art, technology and science converge.”

Ottino has spent his career crossing those boundaries. One of the antecedents of The Nexus is something he calls “whole brain engineering,” a program he developed at Northwestern that is designed to teach not just the quantitative skills commonly associated with engineering but also the qualitative and creative skills associated with artmaking. Other schools—Harvard, for example—want to replicate it.

To illustrate what can happen when the “whole brain” is fully engaged, Ottino and Mau point to 15th-century Florence and Rome, when a “Renaissance man” was someone who was just as conversant in math as in myth, able to work out the structural challenges of bridge construction one day and paint a scene from Greek mythology the next. They point to examples like Galileo, who may be known for his earth-shaking discoveries in physics and astronomy but was only able to explain them fully with the drawing and painting skills he learned at the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno in Florence. Brunelleschi was a goldsmith, yet he was hired to build the biggest dome in the world. Through his mastery of perspective and geometry, he contributed to key areas in what we now think of as science.

But within the Renaissance lay the seeds of the Enlightenment. Church doctrine gave way to scientific inquiry and divine mystery to the power of empiricism. Art, technology, and science split into separate domains, each with its own cultures, codes, and rules. Over the last 400 years, the silos have hardened.

Because this notion of crossing the boundaries of classical knowledge is so core to The Nexus, the authors provide several examples of individuals throughout the last 400 years who possessed the ability to jump the silos, or, as Ottino put it in a recent interview, “to look at things through more than one pair of glasses.” People like Louis Pasteur, who was an accomplished artist as well as a scientist. Or physicist Niels Bohr, who used cubist painting to explain aspects of quantum theory.

The list is short, for as computer scientist, designer, and Microsoft Research partner Bill Buxton (himself a silo jumper) once said to Bruce Mau, you can’t have a Renaissance man anymore because knowledge domains are too vast to be contained in one person—but you can have a Renaissance team. So what would such a team look like? What would be the bridge between right- and left-brain domains?

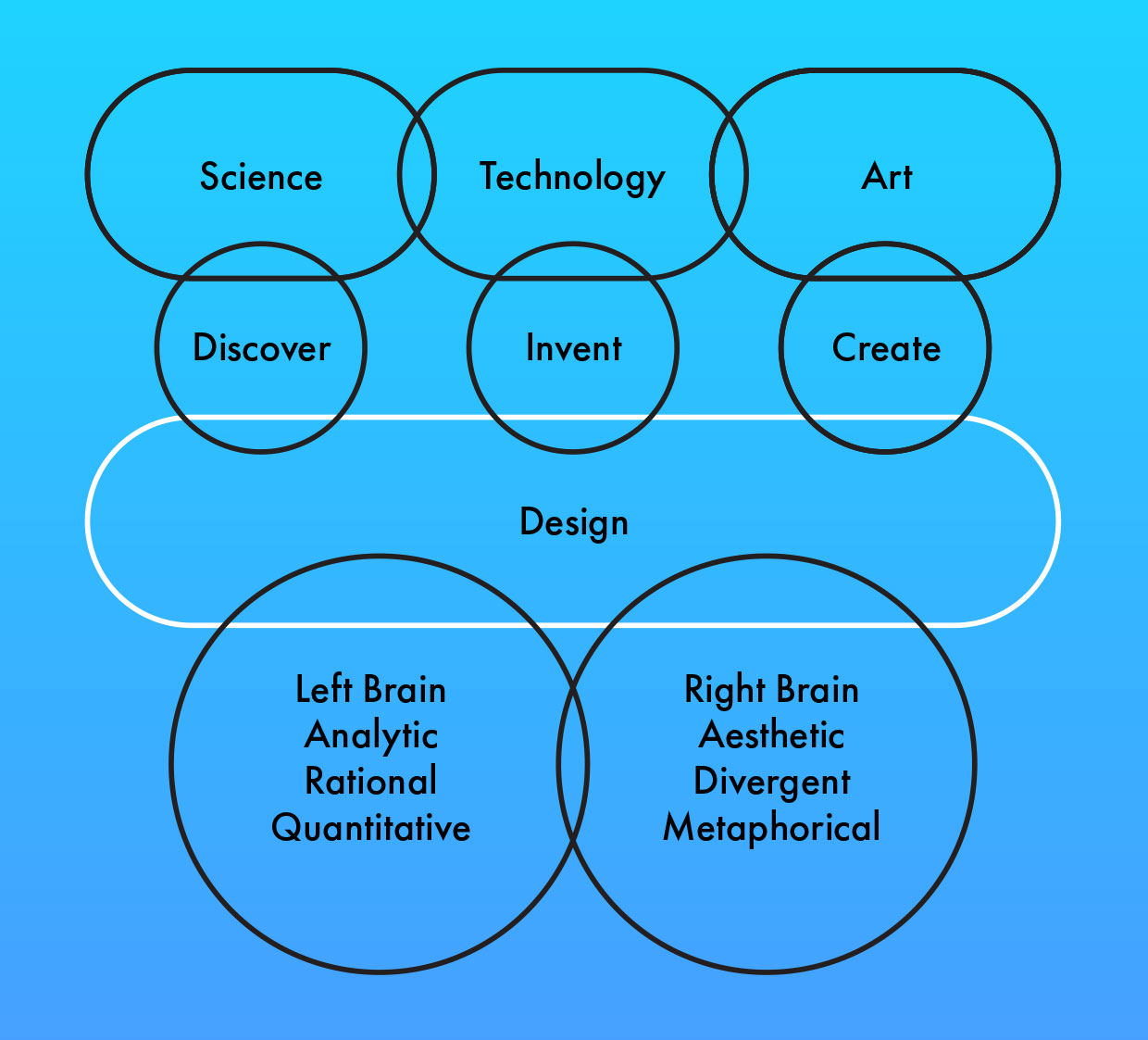

If there is one diagram in this richly illustrated text that answers that, it can be found on page 185. Across the top are the three knowledge domains and their core functions; across the bottom, the two sides of the brain and their core attributes; and overlapping top and bottom, crossing all three domains and both hemispheres in Venn-like fashion, is design.

While the diagram can be broken down into its constituent parts, no one part can be used to explain the whole. When held together by the unifying element of design, its structure suggests a gestalt. This is echoed in the words of Don Norman, cognitive scientist, design icon, and author of The Design of Everyday Things, who has said of The Nexus, “The book itself is autological, an embodiment of the concept it preaches, a brilliant example of why the convergence of disciplines is critical and essential to tackling the complexity of the world.”

This ‘convergence of disciplines’ requires a mind that is capable of simultaneously apprehending contradictory concepts. This mode of thinking juxtaposes a thesis with an antithesis to arrive at a satisfactory synthesis. Hegel referred to it as the ‘dialectic’; design thinkers call it ‘creative collision’; Sergei Eisenstein called it ‘montage’; business guru Roger Martin calls it ‘the opposable mind’. Ottino and Mau call it ‘complementarity’ (see sidebar). It is an indispensable component of the innovator’s toolkit, and for most people it is a skill that requires training, discipline and open-mindedness. Anyone can learn it, but it is only the rare individual who is naturally capable of such intellectual gymnastics.

As a visual artefact, this book’s autological properties are on full display. It would not be inaccurate to say that Bruce Mau has historically been more inspired by the principles of cinematography than of graphic design, bringing to the printed page the editing skills of a Sergei Eisenstein or a Chris Marker, both of whom Mau counts as significant influences. Mau is known for his masterful use of montage, a skill he developed while working on Zone Books in the 1980s and ’90s and which is most famously visible in S,M,L,XL, the 1,376-page “novel about architecture” he co-authored with Dutch architectural iconoclast Rem Koolhaas in 1996.

The Nexus opens and closes on stunning 18-page sequences of dramatically juxtaposed images, perfectly demonstrative of the designer’s facility with the form of the montage. Upon opening the book, the reader encounters a bouquet of exotic flowers placed in low earth orbit and photographed against the black expanse of space, followed by a photomicrograph of a snowflake, then a garment made of fabric that mimics the selae structures found on the wings of a Madagascan sunset butterfly, then a robot carving a replica of Greek statuary out of a piece of Carrara marble, and the interior of the SpaceX Dragon command module. Mau and Ottino, who painstakingly collaborated on the selection of over 200 images that populate the 360-page book, wanted to replicate the effect of the opening and closing credits of a movie.

The opening sequence is followed by a table of contents that is 22 pages long. Each of the book’s chapters gets a page that includes the title, a brief overview of its contents, and a series of subtitles, each with a one-sentence summary of its specific content. This may seem excessive, but the authors claim it was done that way out of respect for the reader, who may use the summaries as a means of accessing specific topics of interest without having to read the whole book. Throughout, the content of the images is a carefully curated mix of art, design, science, and technology.

As Mau explains it, “We did it this way because what you’re really designing is not the book but the experience that someone’s going to have when they interact with the book. And the guiding principle of everything that we did was for readers to have a Nexus experience.”

By now you may have asked yourself who should read this book. The authors have said that “for anyone in this highly complex world who is looking to succeed at making something new, whether that’s a policy, a product, or a service, The Nexus is a way of understanding this new context and how to work there.” But if you read closely enough, while there is no section dedicated to it, Ottino makes several references to the role and importance of leadership.

One word that is absent from this text is “politics.” Science is based on discovery, art on creativity, and technology on invention—three attributes absent from today’s political discourse. The political will to augment our thinking just isn’t there yet, despite the existential threats that are growing by the day.

As Brian Cox, advanced fellow of particle physics in the School of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Manchester, said recently, “It may be that the growth of science and engineering inevitably outstrips the development of political expertise, leading to disaster. Intelligent life destroys itself as soon as it becomes advanced. We could be approaching that position.”

Ottino and Mau are far more sanguine than Cox regarding our capacity to understand and avert disaster. As Mau has often said, given these threats, we have no choice but to be optimistic.

Leadership at The Nexus: Core Concepts

Complementarity: embracing opposites

Complementarity is the ability to embrace opposites. It was a concept originally introduced by physicist Niels Bohr to explain the proposition that in quantum theory, something can be two things at once. When you think of light, for instance, it behaves as both a wave and a particle. As F. Scott Fitzgerald once said, “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” Roger Martin, former dean of the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto, calls this ability the “opposable mind,” and in his book of the same title he proposes that “the richest source of new insight into a problem is the opposing model.” Early in The Nexus, Ottino identifies the ability to embrace opposites as an essential quality of leadership.

Emergence: removing boundaries

Taken from complex systems theory—a field that has been central to Ottino’s research over the years—emergence happens when boundaries between previously separate knowledge domains are removed, thinking spaces expand, and entirely new things emerge. Creating the conditions that allow for successful emergence is not only a prerequisite for innovation but another key component of the leader’s job.

Complex versus complicated: There’s a difference

Complicated systems, such as a nuclear submarine, a mechanical watch, or a Boeing 787, are designed from the top down. Their components can be understood in isolation, and the whole, which can be reassembled from its parts, is designed for all its components to work in unison. But complicated systems are not adaptable. One defect can bring the whole system down. Emergence is impossible in complicated systems. Complex systems, on the other hand—power grids, supply chains, biology, the internet—all involve a subtle, intricate balance between the “system” and our actions upon it. Climate change is an obvious example. Changes come from the bottom up, but unlike complicated systems, complex systems are adaptable. Looking at the parts in isolation gives no clue about the whole; in fact, focusing on the parts misses the whole. Again, understanding complexity is a core competence of leadership.

The map and the compass: when to use them

Maps work well in stable, well-understood environments, where nothing changes. But in complex, unstable environments, a compass is far more useful than a map. Managers operate with maps; leaders operate with a compass. As Ottino puts it, “The role of leadership can be imagined as aligning a group of randomly distributed individual compasses into a single larger compass. In fact the ability to create a global compass may be the essence of leadership.”

0 Comments