Photo: Joint Task Force Guantanamo

In January 2002, the United States began sending prisoners to Guantánamo Bay. That same month, President Bush said that prisoners from the war in Afghanistan would not be afforded all protections of the Geneva Conventions. They would be treated “humanely,” he said, in the “spirit” of the Geneva Conventions. “We’re adhering to the spirit of the Geneva Convention…. It’s a very important principle,” Bush said.

This “spirit of the Geneva Convention” provided few protections for prisoners in U.S. custody. Before General Geoffrey D. Miller was sent from Guantánamo to Iraq to “Gitmoize” the infamous Abu Ghraib prison, he had instituted nudity, shackling in stress positions, sleep deprivation, and other infernal tortures we have come to know as “enhanced interrogation,” all approved at the highest levels of the U.S. government. F.B.I. agents subsequently reported finding prisoners chained naked to the floor in 100-degree heat, without food or water, where they had “urinated or defecated on themselves.” One F.B.I. report described a prisoner, naked, chained to a bolt, “almost unconscious on the floor with a pile of hair next to him. He had literally pulled his own hair out throughout the night.” Guards practiced “the Frequent Flyer Program,” hauling prisoners from their cells and moving them from cell to cell sometimes 10 times a day for weeks on end, depriving them of sleep.

All of this has made prosecutions difficult. Torture—and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment—are illegal. Evidence obtained by coercion may not be introduced in court. The 2006 Military Commissions Act (amended in 2009) attempts to mitigate the effects of torture on legal proceedings, but it hasn’t worked. There are so many problems with the Military Commissions themselves that six military prosecutors have resigned in protest. Few of the prisoners detained at Guantánamo have been or will be tried through them. There are at least 50 “forever prisoners” there; President Obama has said they will be held permanently without charges or trial. Their cases are also compromised by torture.

The Military Commission trial of Khalid Shaikh Mohammed and four co-conspirators allegedly involved in the 9/11 terror attacks was halted this February because one of the accused, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, recognized the war court linguist as the same interpreter the CIA had used while he was being tortured at a “black site.” Hearings resume in October and are scheduled to continue through September 2016—for a crime committed in 2001. The trial of Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri is currently suspended. He was captured in 2002 and is charged with masterminding the bombing of the U.S.S. Cole in 2000. Both Khalid Shaikh Mohammed and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri were tortured while in U.S. custody.

Last October, U.S. District Judge Gladys Kessler ordered the Department of Justice to release videos of the force-feeding of Guantánamo inmates, as demanded by the attorney of one victim and several news organizations. The Obama administration has stalled for nine months.

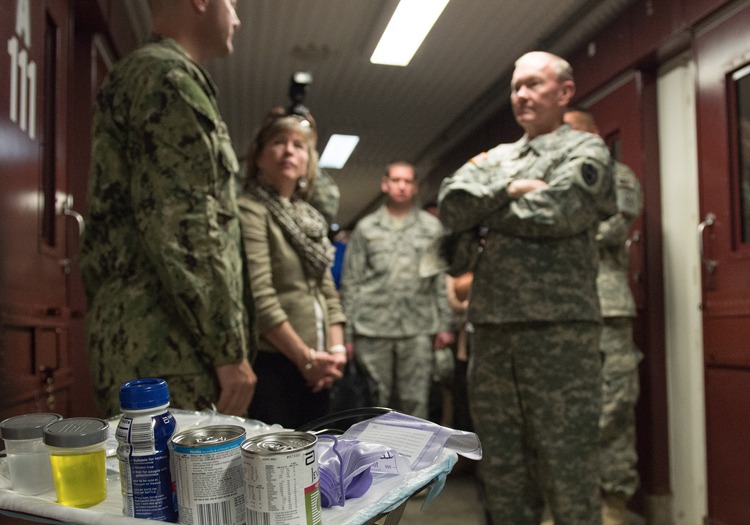

Authorities at Guantánamo have been force-feeding hunger strikers for years. Prisoners, sometimes in diapers, are placed in restraint chairs and a tube is inserted in the prisoner’s nose, several times a day, often resulting in vomiting and bleeding. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture, Juan Méndez, called the practice, “tantamount to cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment.”

One hundred fourteen men are still imprisoned at Guantánamo, most have been there over a decade without charges or trial. Fifty-six have been cleared for release, most of them five years ago. More people have died in Guantánamo (nine) than have been convicted in Military Commissions trials (eight).

These men are not numbers or abstractions. Tariq Ba Odah is not a number. He has been held since 2002 without charges. He was cleared for release five years ago and has been on a hunger strike for eight years. He weighs 74 pounds. On August 15, the Justice Department denied his lawyer’s petition to have him released to his family in Saudi Arabia. The Justice Department released its denial of the petition in a sealed finding, citing its desire to protect his privacy because it deals with his “medical issues.”

The cost of our prison at Guantánamo is now more than $5 billion and counting. It costs almost $500 million per year to maintain the current prisoner population.

President Obama’s attempts to close the detention facility have been blocked by Republicans in Congress. He can, however, expedite the release of those prisoners cleared, end the practice of forced feeding, and order the release of videos that have documented this dehumanizing process.

And continue to press his case with the American public.

Bonnie Tamres-Moore is an anti-torture activist working with Interfaith Action for Human Rights.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks