George Orwell wisely observed that our understanding of the past, and the meaning associated with it, directly influences the future. And as the unprecedented public feud between the CIA and Congress makes clear, there are still significant aspects of our recent history of state-sponsored torture that need examination before we put this national disgrace behind us.

Important questions remain unresolved about the U.S. torture program in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. And the four-year, $40 million Senate Intelligence Committee report on CIA torture is unlikely to provide sufficient answers, even if it’s ever declassified and released.

For example, what will be done about doctors who helped create U.S. torture programs and participated in their implementation? And is there any evidence that cruel, inhuman, and degrading practices continue under official policy, even to this day?

The question of whether American health professionals previously involved in military torture programs should be allowed to quietly and freely continue their careers came to a head recently when it was revealed that the American Psychological Association (APA) refused to pursue ethics charges against psychologist John Leso.

According to official and authoritative documents, Dr. Leso developed and helped carry out “enhanced interrogation” techniques at Guantánamo Bay in 2002. Importantly, the APA hasn’t disputed Leso’s role in the interrogation of detainee Mohammed al-Qahtani, an interrogation that included being hooded, leashed, and treated like a dog; sleep deprivation; sexual humiliation; prolonged exposure to cold; forced nudity; and sustained isolation.

Why isn’t the American Psychological Association pursuing ethics charges against psychologist John Leso for abuses he helped carry out at the Guantánamo prison?

In a subsequent investigation, Susan Crawford, a judge appointed by then-Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, characterized this treatment of al-Qahtani as “life-threatening” and meeting the legal definition of “torture.”

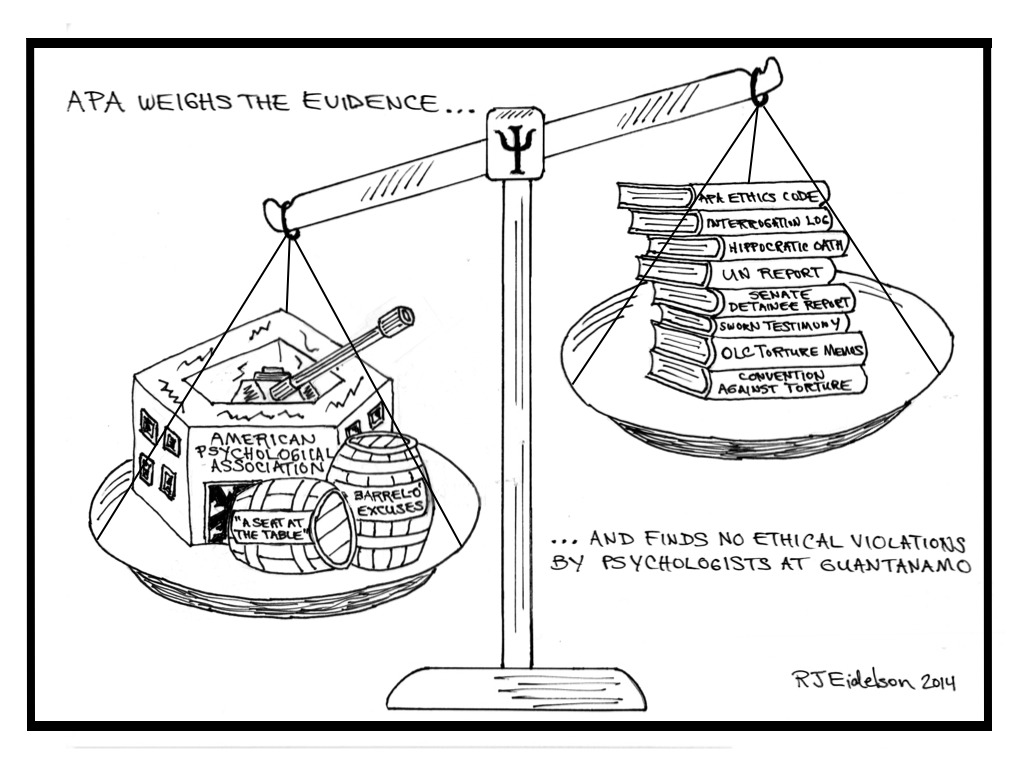

Over almost seven years, the APA—whose leadership has nurtured strong connections with the military and intelligence establishment—never brought the case to its full Ethics Committee for review and resolution. In defending this decision a few weeks ago, the APA board released a statement explaining that a handful of top people with classified military access had determined that there was nothing unethical about Dr. Leso’s actions and that the case should be immediately closed.

What exactly is the interest of the leaders of the world’s largest professional association of psychologists in blocking investigation into torture? And should psychologists who participated in torture have this dark chapter of their careers wiped clean without censure?

Ethical imperatives to “do no harm” and sanctions for psychologists who break the rules—from sleeping with patients to insurance fraud to not informing research subjects of their rights—exist not only to protect the public but also to provide clear guidance to professionals faced with moral dilemmas. Yet when considering ethical complaints, the APA apparently takes involvement in torture less seriously than these other transgressions.

If such ethical parameters are effectively nullified, what kind of future might we expect?

Here’s an equally important question: Has U.S. torture really ended? While the Obama administration made an early display of banning some of the worst techniques that had been given the official seal of approval under Bush and Cheney, such as waterboarding, the Pentagon continues to engage in cruel, inhuman, and degrading practices.

As the lawsuit brought this month by Guantánamo prisoner Emad Abdullah Hassan in federal court makes clear, the force-feeding of hunger strikers there is continuing despite a military blackout since December on the number of inmates engaged in that protest. Human rights and medical organizations have widely denounced this brutal practice.

Before U.S. psychologists and other Americans tell ourselves it’s time to put our history of torture behind us, we should take a hard look in the mirror.

What does it mean for our society to allow health professionals who have been involved with torture to subsequently practice with impunity? Like all civilized societies, we must reckon with past and present truths — if we want to be in control of our future.

Yosef Brody is a clinical psychologist and president-elect of Psychologists for Social Responsibility PsySR.org

0 Comments