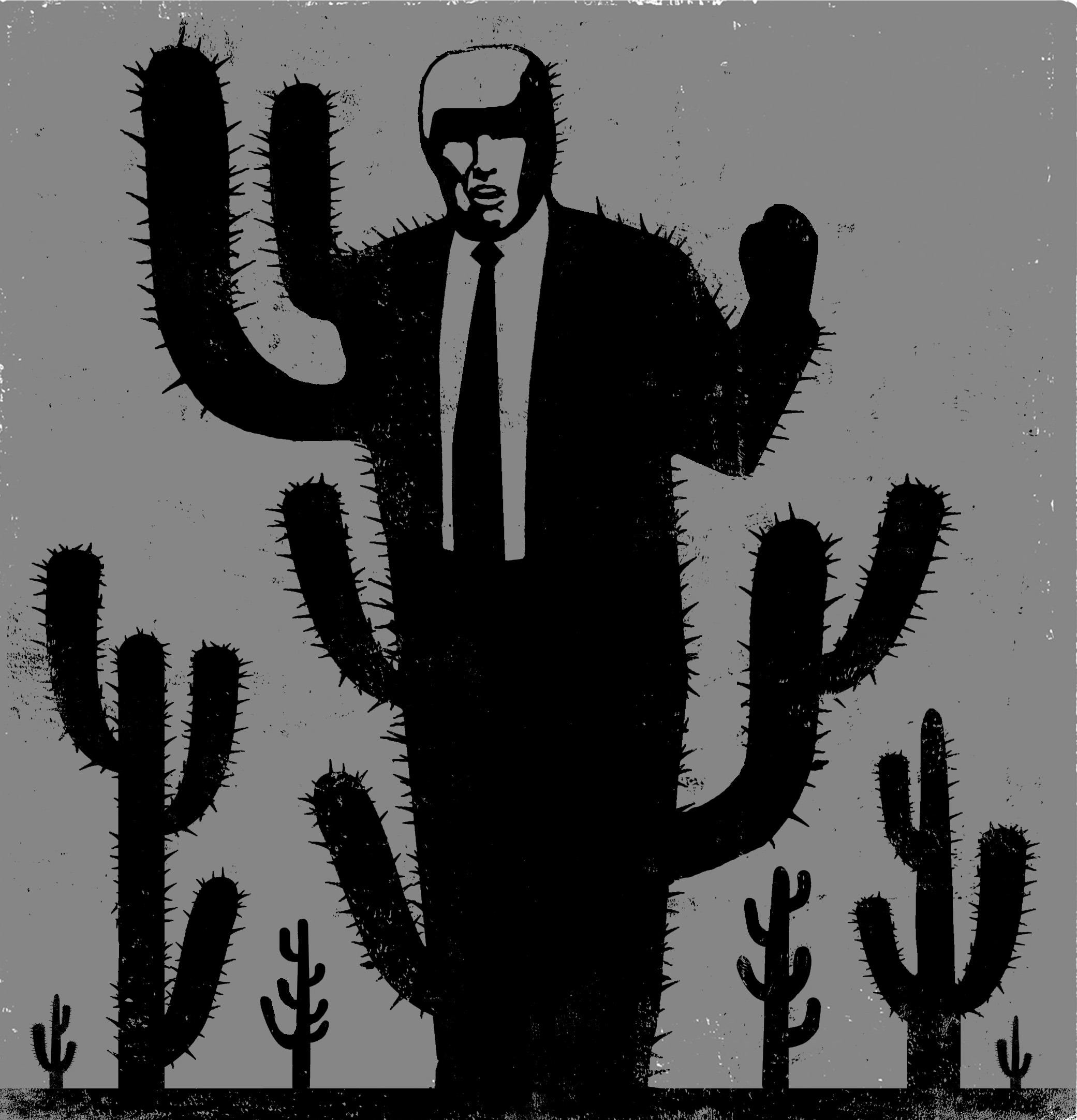

Edel Rodríguez

Mexico City

Donald Trump has connected with the Mexican public in a way that no other American politician ever has. Talk to a cab driver, a group of kids at a gay pride rally, a high school teacher, a woman scratching out an existence selling churros on a street corner—everyone, it seems, is offended by the crude slurs Trump has aimed at this country. And the Mexican vox populi is consistent—offended and angry—about Trump’s “Big Beautiful Wall.”

Less discussed, and far more threatening to Mexico, are the policies a President Trump would pursue. One in particular, impounding remittances, the money Mexicans living in the United States wire home, would inflict enormous economic pain.

“Everyone on this street teaches students who survive on remittances from the United States,” José Alfredo told me. Alfredo was a “work-stoppage coordinator” for the CNTE, a national teachers union. There were about 1,000 teachers milling about a tent encampment that stretched for blocks in both lanes of Bucareli Avenue, just off the city’s grand Paseo de Reforma.

Alfredo, whose last name I omit because the federal government has been ruthless in its response to the work stoppage, was standing in front of a sagging plastic banner decrying the education secretary’s reform plan, and a hand-lettered poster that read “Austerity Destroys Families.”

It was easy to get the union leader riffing on the slurs that have set Mexican-Americans and Mexicans in the United States on edge: “They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.”

“He is a xenophobe and racist who doesn’t respect the unity of our two nations,” Aldredo said. “He has insulted an entire nation.”

When I ask Alfredo about Trump’s threat to impound remittances, his answer is stark.

“People will go hungry.”

The public school teachers camped out on Mexico City streets in mid-May were bused in from the agrarian southern states of Chiapas, Guerrero, and Michoacán. Places where Trump’s threat to cut off remittances are a serious threat. At the most microeconomic level, the policy Trump is proposing will have a dramatic effect. People will go hungry.

“He is a xenophobe and racist who doesn’t respect the unity of our two nations.”

Trump’s policy statements regarding Mexico are widely known. He says he will deport all undocumented Mexicans living in the United States, build a wall to ensure they can’t get back in, and make the Mexican government pay for the wall.

Complex policy reduced to a Trump trope: Impound wire transfers of workers’ money to Mexico until the Mexican government meets its “obligation.”

“It’s an easy decision for Mexico,” Trump told The Washington Post. “Make a one-time payment of $5–$10 billion to ensure that $24 billion flows into their country year after year.”

Last year, Mexicans living in the United States wired $24.8 billion—two percent of Mexico’s GDP—in remittances to families they left behind when they came to the United States. By comparison, oil exports provided Mexico $23.4 billion.

“Blocking remittances would be very destructive, very destabilizing,” María Marván Laborde told me.

Marván Laborde, a newspaper columnist and political scientist who recently served on the Federal Election Institute and now teaches at Mexico’s National University (UNAM), is one of several policy intellectuals I asked about Trump’s Mexico policy.

“It would have the greatest impact in the Mexican countryside,” she told me in an interview in her campus office. “There are hundreds and hundreds of towns that are entirely dependent on remittances.” The transfers, she added, have lifted entire rural communities out of poverty.

At the Inter-American Dialogue, a Washington think tank, Manuel Orozco tracks the transnational transfer of money. “Six million households,” he said, “nearly 20 percent of all households in Mexico, receive more than 50 percent of their income from remittances, which is not a welfare program.”

The $24 billion figure Trump cites suggests he would impound all the money that all individuals—undocumented, documented, naturalized U.S. citizens—send to Mexico. Would Trump Treasury Department officials impound a few thousand dollars Columba Bush might wire to her aunt, María Diega Mendéz, a hard luck story Univision tracked down when Jeb was a “pre-candidate,” who earns $6 a day as a fruit peddler in Leon, Guanajuato?

Whether it’s a Bush in-law or another septuagenarian scrambling to earn a few pesos in a country with no social safety net, impounding remittances will inflict pain.

Beyond starving a few million day laborers, and rural Mexicans still struggling with NAFTA’s economic dislocations, Trump’s strong-arming would rattle the national economy.

Marván Laborde reads the GOP candidate’s statements about the border wall, immigration, and the U.S. trade deficit with Mexico as a broader assault on established relations between the two nations.

“I think he wants to change the way we conduct our trade,” referring to Trump’s comments about “lousy trade deals” and NAFTA. “These trade relationships have taken 20 years to establish,” she said. “They cannot be undone in four years, even if there is a new Washington consensus on a different kind of international trade.”

She described some of Trump’s Mexico policy positions as “a fantasy,” that can never be implemented.

“Nonetheless,” she added, “should he arrive in the White House, Trump’s aggression, his political confrontation with Mexico, could be very damaging for both countries.”

The aggression and political confrontation already are damaging. Trump’s candidacy alone has dinged the Mexican ecomomy. The peso fell to a historic low in trading against the dollar on May 4, on news that Ted Cruz ended his campaign. It wasn’t Cruz’s exit that rattled currency markets, but the realization that Trump was the Republican candidate. That’s how Gabriela Siller, director of financial analysis at Banco BASE, explained it in a May 4 finance bulletin.

“The peso started its slide [to 18-to-the-dollar] Tuesday night, after Senator Ted Cruz abandoned his campaign for the Republican Party’s presidential nomination, clearing the path for Donald Trump, who has based his campaign on comments against Mexicans and U.S. trade agreements with Mexico,” Siller wrote.

If Trump were to deliver on his campaign promises, his first year in office could mean a 4.9 percent decline in Mexico’s Gross Domestic Product, because of lower exports to the United States—and decreased private consumption at home, caused by lost remittances, according to Siller.

“Deportation on the scale Mr. Trump describes is almost impossible for any nation.”

North of the border mass deportations (of 3.5 percent of the total U.S. population according to PEW Research) would shrink the labor force by 6.4 percent and ultimately reduce U.S. GDP by 6 percent, according to American Action Forum, a conservative economic think tank led by Douglas Holtz-Eakin, who directed the Congressional Budget Office and was chief economic advisor to John McCain’s presidential campaign. “While this impact would be found throughout the economy, the agriculture, construction, retail, eating and drinking sectors would be especially strongly affected,” according to AAF.)

Trump’s campaign has Mexicans returning to the famous quote by fin de siècle dictator Porfirio Díaz: “Poor Mexico, so far from God, so close to the United States.” Trump opened his campaign with his “rapists, drugs, crime” attack on Mexicans—then in his first policy paper outlined his plan to rid the country of the problem: Immigration Reform that Will Make America Great Again.

In the “Make Mexico Pay for the Wall” paragraph of Trump’s six-page immigration white paper he describes exporting criminals as the official policy of the Mexican government: “For many years, Mexico’s leaders have been taking advantage of the United States by using illegal immigration to export the crime and poverty in their own country . . .”

A President Trump would expedite deportation of “criminal aliens.” All aliens, undesirable and desirable, would follow. “We have to get them out. If we have wonderful cases, they can come back in but they have to come back in legally.”

The 11 million would be rounded up and deported so fast, Trump said last summer when he used the issue to emasculate Marco Rubio, Ben Carson, and Jeb Bush, it would make “your head spin.” The mass-deportation project will be wrapped up in 18 months, he claimed.

“First of all, it’s a fantasy,” Cecilia Imaz Bayona told me. “Deportation on the scale Mr. Trump describes is almost impossible for any nation.”

Imaz Bayona is a professor who has advised the Mexican Senate on immigration policy and has written a book on Mexico-U.S. immigration. Her 280-page study documents the extent of Mexico-U.S. emigration—96 percent of Mexican municipalities are in some way involved in the Mexican diaspora. And it includes a few concepts that would set Trump’s comb-over on fire, and easily fit into one of his xenophobic rants: for example, her description of an ingrained “culture of emigration” in certain regions of Mexico.

She believes Trump’s statements on Mexico are like his Twitter blasts, calculated to create as big a bang as possible, but divorced from public policy reality. “This idea of deporting 11 million persons. Absurd and impossible. It would require a force 10 times larger than what the United States now has controlling the border.”

The American Action Forum is closer to Imaz Bayona than Trump on mass deportation logistics. Not 18 months, but 20 years to track down, detain, and deport the millions Trump would target, and at a cost of $100 billion to $300 billion to the American taxpayer.

Yet in the end, Mexico’s economy and its public-sector spending will be damaged the most by Trump’s plans.

It was cuts in education funding that brought the contingent of public school teachers to the capital in May. After being forcibly relocated from the streets they initially occupied, they were moved to a plaza a few blocks west of the National Cathedral. After a night camping on the cobblestones of Plaza Santo Domingo, they were rousted at 3 a.m. by hundreds of body-armored riot police, loaded onto chartered buses, and escorted back to the provinces.

They went home empty-handed.

0 Comments