On a Sunday morning in September, Maryland Democratic gubernatorial candidate Ben Jealous is in church—of course.

In fact, it is his third Baltimore-area church service that morning, beginning at Woodlawn’s sprawling, suburban Morning Star Baptist at 7 a.m., moving on to the nearby New Psalmist Baptist megachurch with at least a thousand congregants by 9:30 a.m., and finally arriving at noon to sit in the rows of folding chairs at Rev. Jamal Bryant’s Empowerment Temple in the city’s downtrodden Park Heights neighborhood.

Though Jealous probably needs no introduction at the Temple—he has been here many times and indeed has been organizing alongside Rev. Bryant since both men were in their 20s—the reverend, because that’s how this famously loquacious man rolls, can’t resist a wind-up.

“I’m just surprised we survived the summer,” the reverend says. In his shiny black suit with white cuffs and a clergy collar, he is already sweating. “Can ya’ll believe that? We made the whole summer and Trump’s still not in jail. Can you believe it?” Congregants snicker. But he is just getting started. “I mean, between Memorial Day and Labor Day we thought something was going to happen.” Pause. Wait for it. “God owes us something by Halloween!”

When the laughter dies down, Rev. Bryant, standing before the triptych of oversized Black Lives Matter protest photos that form the altar’s backdrop, shifts his attention to the recent Florida primary where black progressive Andrew Gillum’s victory was a surprise upset that week. “The whole nation was jubilant over the election in Florida of our dear brother who is now positioned to be the first black governor for the state of Florida.” The congregation cheers. “I’ll tell you. It is good to be grown. I can now jump on my own bed. If I was still living with my mama, she would’ve smacked me. But I was jumping on my bed looking at those election results, and it dawned on me, Why am I that excited about Florida when we getting ready to have the same thing happen in Maryland?” People shout some “Amens,” but the enthusiasm remains muted for the reverend’s taste. “I need ya’ll to vote cuckoo for Cocoa Puffs. Come on! We gotta tear da club up—the next governor and the first black governor for the state of Maryland is in church today. Help me thank God for Benjamin Todd Jealous. Come on, ya’ll gotta make some real noise.”

The crowd roars as Jealous stands up from the front row; he waves, he smiles, he is loved—here, anyway.

The Reverend Jamal Bryant is right: Come November, Jealous must indeed rally voters to “make some real noise.”

Jealous, 45, is being touted nationally as part of the progressive wave of young candidates with surprising upsets in Democratic primaries this summer. In June, he rose to the top of a field of six Democrats in Maryland’s gubernatorial primaries, beating out the expected winner, Prince George’s County Executive Rushern L. Baker III, who had the backing of the state Democratic establishment and major endorsements, such as former Gov. Martin O’Malley, state Senate President Thomas V. (Mike) Miller, and U.S. Senator Chris Van Hollen.

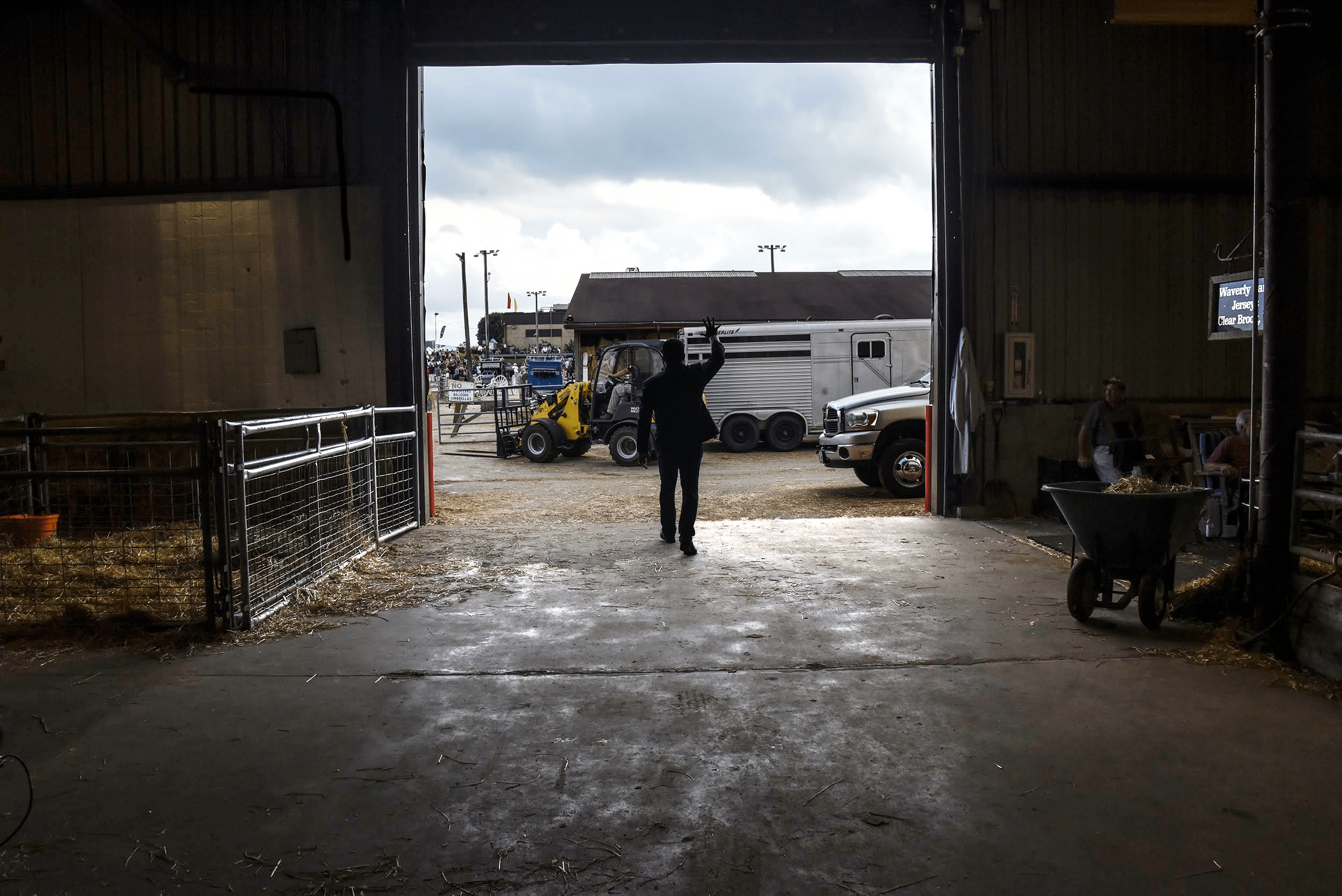

Photo Credit: J.M. Giordano

But alongside his running mate, former Maryland Democratic Party Chairwoman Susie Turnbull, Jealous crisscrossed the state announcing his plans for single-payer healthcare, free community college tuition, police reform, raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour, and legalizing weed. “Voters may think of Mr. Jealous as the Bernie Sanders candidate in this race,” Baltimore Sun editorial writers shorthanded in their endorsement of Jealous. And in the primaries anyway, Democrats indicated they were tired of centrist, lackluster Democratic establishment candidates. To the astonishment of many, Jealous won every county in the state but two.

In liberal Baltimore City, where 43 percent of Democrats voted for Jealous compared to 19 percent for Baker, this was less remarkable. But Baltimore County, where Dems are generally more conservative, also went for Jealous, with 42 percent of voters pulling the lever for him over Baker, who scored only 19 percent of the votes. In Montgomery County the margin was smaller, with Jealous garnering 36 percent to Baker’s 32 percent. Only in rural Calvert County and Baker’s own Prince George’s County did Baker take the lead. In Prince George’s County, Baker took 50 percent of the vote while Jealous got 38 percent.

By the end of the summer, endorsements of Jealous had snowballed as multiple unions came on board. Senators Kamala Harris, Cory Booker, and Bernie Sanders, as well as others, such as former Vice President Joe Biden, all back him.

“This campaign is about seizing the moment to build a movement to make sure that everyone moves forward, no matter what happens in Donald Trump’s Washington,” Jealous said in his victory speech.

Jealous is running a grassroots campaign. And in that spirit, instead of talking to the echo chamber of pundits, who in any case called this race wrong in the primary, I joined Jealous on the campaign trail to gauge his reception among voters.

There, Jealous hews closely to what he calls “kitchen table issues” and insists he is not into divisive politics. “The old lines between urban and rural matter less,” he says. “White, black, brown, Asian, Native American matter less. People of different faiths matter less. What matters is, are we moving forward? Do we have a plan? Can we fix what’s holding all of our families back? What we’ve chosen to do in this campaign is to do what FDR did and simply present people with solutions that rise to the scale of the problems we’re all facing. And what we found in the primary and what we’re finding in general as we’re moving through the crowd today is that people are ready to come together and move forward.”

In Maryland, he says, divisiveness won’t work anymore and he dismisses attack ads as tired tactics, temporarily giving candidates here a bump in the polls but ultimately costing votes. “These hateful ads they’re running, those work, but you know what works better?” he asks, then answers, “Giving people a positive vision for how we move forward together. And that’s our discipline, that’s our faith, that’s how we won the primary, that’s how we’ll win the general.”

As a longtime activist and former president and CEO of the NAACP, he has a policy wonk’s deep knowledge of the issues but an activist’s flair for distilling them into a chant-sized phrase. And he can read a crowd.

Back at the Empowerment Temple on that Sunday morning, when Jealous takes the mic from the reverend, he alludes to their long history of organizing together, “around one issue more than any other, to finally stop the killing of unarmed civilians by the police.”

If you are from Baltimore, there is a linguistic nuance here. The phrase among activists—and of course, the more accurate phrase—is “unarmed black men.” Similarly, Jealous’s campaign website references the post–Freddie Gray “riots.” Among activists, intent on shifting the emphasis from Gray’s 2015 death as the isolated cause of a riot to the incendiary culmination of decades of police abuse, the term is typically “uprising.” But Jealous code-switches. “Uprising” is the term Jealous uses in person when I speak to him.

And at the Empowerment Temple that morning, standing in front of the Black Lives Matter protest photos, he understands this as an “uprising” crowd that is deeply concerned about police reform. It is easy to see why he deftly recasts the police union’s endorsement of his opponent as an asset. “And you know, people say, ‘Are you surprised that almost all the unions have endorsed you but a few haven’t—like the Fraternal Order of Police?’” he asks the congregation. “And I said, ‘Man, if you ever see the FOP endorse an NAACP leader to be governor, tell me, so—.” He pauses, grasping for a way to end that sentence. “So I can buy a lottery ticket that day!”

He assures people that he is committed to treating the police fairly. “Just as much as I am committed to making sure that everybody is treated fairly, everybody is held accountable, and we finally stop this scourge that is our young people being killed by the very people that have sworn to protect and respect them.”

“So let us get out there and tell everybody we like, and even the folks that we don’t like, to turn out and vote. Because if we turn out a million voters . . . we will win and be moving forward again. Thank you and God bless.”

“Give a big hand, please,” the reverend says, taking back the mic to thunderous applause. “That’s our next governor. Tell everybody at work, at the cookout, that’s my friend.”

The Jealous campaign strategy is not rocket science, nor is it news to savvy readers of the political scene. First and foremost, Jealous must persuade one million Maryland Democrats to show up at the polls, ideally from the state’s central, densely populated corridor stretching from Baltimore to D.C., and they must flick those levers with a “D” after their names with a fervent, consistent anti-Trump tremor in their souls.

It could happen.

The snag? It is proving hard to cast the state’s centrist Republican governor as a Trump ally. After all, Gov. Larry Hogan famously refused to go pay homage to Trump at the GOP convention in 2016. “I don’t even want to be involved,” he told an AP reporter at the time. “It’s a mess. I hate the whole thing…. I don’t like the dialogue. I don’t like the things that are going on, and I’m sick of talking about it, because it’s not anything I have anything to do with.”

Of course, it made strategic sense, even then, for Hogan to distance himself from this Republican candidate so reviled by state Democrats. In Maryland, Democrats outnumber Republicans 2 to 1, so jabbing out his elbows for a little distance from Trump behooves him. This summer, Hogan railed to Frank Bruni in The New York Times, “We’ve been attacked since the day [Trump] was inaugurated, since the day he was elected. It’s Hogan and Trump, Hogan and Trump, Hogan and Trump.” And he fought back: “Ben Jealous—let’s bring it back home—is the nominee for the Maryland Democratic Party to run for governor. He’s a far-left socialist who wants to increase the state budget by 100 percent, increase taxes by 100 percent, free everything.”

Gov. Hogan, whose approval rating ran between 60 and 70 percent this summer, is doing what he can to shift the conversation from the national scene to the local one. “The job of governor doesn’t have much to do with what’s going on in Washington, but this guy doesn’t know a lot about Maryland or the Maryland state government or budget, so he likes to talk about far-left issues that he thinks he can turn into a national race,” Hogan said, hitting his favorite theme on Brett Hollander’s WBAL talk show in July.

But the Democrats—wisely—are working the Trump connection, and many old timers whose seats are fairly secure are helping. Overnight, on September 11, lawn signs popped up in neighborhoods across Baltimore saying, “Stop Trump. Elect Democrats. Save America.” Or, somewhat ironically given that the party backed Jealous’s opponent in the primary, “Vote for the Democrats.” Paid for by Cummings for Congress—noted in minuscule print at the bottom—the signs don’t even bother to shill for Congressman Elijah Cummings’s reelection in Maryland’s 7th District, where he has held office since 1996 and got 91 percent of the vote in the primaries; they are clearly designed to capitalize on anti-Trump sentiment here with a plea for voters to ride the blue wave.

The Democratic establishment doubtless goes to bed each night praying that Trump endorses Hogan: Please, God, just one tweet about Hogan’s GREAT job as a TRUE AMERICAN.

In many ways, the Sunday campaign sweep that Jealous does from Baltimore City to the counties has symbolic significance and makes strategic sense. He lives in Anne Arundel County and must shore up support in suburban and rural areas, but he gets more bang for his buck in the city, more densely populated with progressives.

And he has family roots—and civil rights, activist roots—in Baltimore that go back to the 1940s when his grandmother worked for Planned Parenthood in the days when that was a radical act (or even more of a radical act). He describes his family’s multigenerational “move from poverty to relative prosperity,” insisting that “it’s been public education that transformed our lives, and that’s why I’m so laser focused on fully funding our public schools and making sure that we end the student debt crisis in our public universities.” He explains, “My mom grew up in McCullough Homes housing projects [in the city]. A generation later, she waved goodbye to me as I flew off to Oxford, England, to be a Rhodes Scholar.”

Like most politicians, Jealous hews to a rags-to-riches script, but he’s got some bona fides. (Unlike, say, our president, who in 2015 famously lamented his rough childhood and measly start-up allowance: “It has not been easy for me, it has not been easy for me,” Trump said, then added, “And you know I started off in Brooklyn, my father gave me a small loan of a million dollars.”) Jealous’s mother, who is black, was one of 10 girls who desegregated Baltimore’s elite Western High School in 1955. His father, who is white, participated in lunch-counter sit-ins in downtown Baltimore during the ’60s. When his parents, both teachers, married in 1966, interracial marriages were illegal, and they were forced to marry in Washington, D.C., then relocate to California.

Jealous himself has been organizing ever since he went to a campaign event for Jesse Jackson at age 14 and got involved in the Rainbow Coalition’s youth vote drive. Later, when he attended Columbia University, he worked with the NAACP legal defense on health care issues in Harlem, fought the university’s plans to eliminate some of its scholarship funding, and was suspended for organizing a protest over the school’s plan to turn the site of Malcolm X’s assassination into a research facility. He worked as a journalist in Mississippi for the Jackson Advocate, an African American newspaper and then, in 2002, headed up the National Newspaper Publishers Association. At 35, he became the youngest national president and CEO of the NAACP. During his tenure, he says that he bumped online membership in the organization from 175,000 to more than 600,000. He has also consistently organized around police reform, ending the death penalty, legalizing gay marriage, and a host of other civil rights issues.

When he left the NAACP in 2013, he joined the investment firm Kapor Capital, which is likely why he scoffed when a reporter asked him in August whether he was a “socialist” on the heels of an attack ad accusing him of this. “Are you fucking kidding me?” he said.

His opponents’ efforts to turn this salty language into a “thing” largely backfired because (1) this was Baltimore, where there is no such thing as “F-bombs” and, on the contrary, the colloquialism endeared him to folks, and (2) it’s awfully hard to ignite a firestorm by lobbing an incivility charge for this with the Tweeter-in-Chief setting the standard.

Indeed, the Jealous campaign professes that it is gleeful to see attack ads being aired this early in the campaign. “Hogan’s in trouble,” Jealous says. “And he’s acting like a politician who’s scared.”

On the flip side, it could just be that Hogan has money to burn—$9.4 million compared to Jealous’s scant $386,000 in cash (as we went to press). This will obviously hobble the Jealous campaign. Perhaps it already has. Several supporters at the Maryland State Fair complained that there were no stickers, buttons, flyers, or lawn signs for them to show their support for Jealous—let alone an advertising blitz.

Instead, the campaign is clearly relying heavily on free publicity. Plus, Jealous has a decent social media presence: 102,000 Twitter followers compared to Gov. Hogan’s 62,000.

And Jealous has been quick to seize the moment with the evolving news cycle. For example, as more than 60 Baltimore schools were forced to send children home during the first week of classes in September, Jealous was out with a video team at the crack of dawn in front of a school pointing out how Gov. Hogan has failed to address the city’s education crisis.

The tactics, in this unpredictable season of surprise upsets, put him within striking distance.

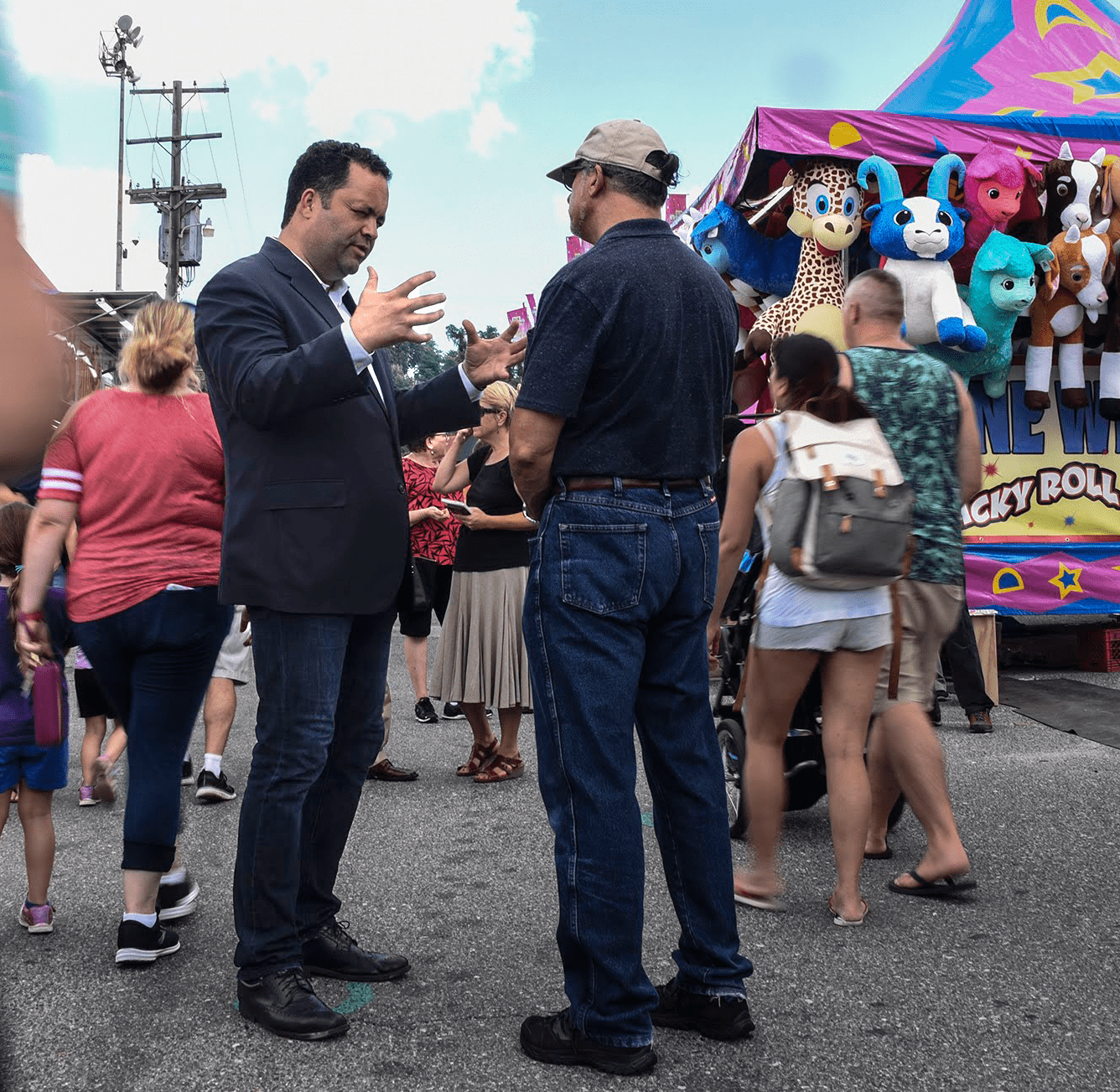

Photo Credit: J.M. Giordano

By 3 p.m. on Sunday, Jealous has left the churches and the city and is in Baltimore County, glad-handing in the oppressive heat of the Maryland State Fair. In this suburban county the demographics are the inverse of the city’s—61 percent white and 29 percent black, compared to Baltimore City’s 63 percent black and 30 percent white, according to U.S. Census data for 2017. The median household income jumps from the city’s $44,262 to $68,989 in the county, and the city’s 23 percent living in poverty drops to 9 percent in the county.

All this is a roundabout way of saying it’s an entirely different scene here. Men in khakis, wearing loafers—sockless—mingle with women in star-spangled shirts and children in unicorn headbands who clutch oversized stuffed dinosaurs. Vendors hawk everything from ponchos to popsicles, and the rousing hymns of the morning have been replaced by a tinny rendition of “Pop Goes the Weasel.” On a loop. An endless loop.

Jealous mingles, introducing himself to the crowd of curious onlookers. He has some campaign staff filming a video of him and, intentionally or not, it is a good ploy, feeding a ripple of speculation among passersby—Who’s that? Is it a celebrity? What’s he running for? He meanders from the games to the rides to the animal pens, wading through the scent of fried food, burnt sugar, and cow manure tangling in the still air. He pauses for a photo with Morgan State University professor Juanita Gilliam, a black woman who voted for him in the primaries; he has her vote in the general election but, she sighs as he walks away, “he is going to have to run real fast to catch up Hogan.”

Jealous introduces himself to a middle-aged white man, Richard Toft, who works in construction, holds a can of beer in one hand, and wears a Led Zeppelin shirt. Jealous gives his talk about “what made FDR great” and how we need “big solutions to big problems,” and Toft listens intently but makes no promises about his vote. Jealous smiles, asks, Has he ever heard Mary J. Blige’s version of “Stairway to Heaven”? He hasn’t.

Photo Credit: J.M. Giordano

Minutes later, Jealous bends down on one knee—wait for the photo—to talk to seven-year-old Chloe King and beams when she says she wants to be a teacher when she grows up. Click. His parents were teachers, he says.

A white man in his 60s wearing khakis and a blue polo spits out as he walks by, “End of the state if that man gets elected.” Jealous doesn’t hear him, or if he does, ignores him. He is gracious, absorbed, and later, sitting in the blistering sun with me for an interview on a set of wooden bleachers overlooking a dusty animal pen, his jacket temporarily removed and hanging from the railing, sweat drenching through his white button-down, he insists he “loves” campaigning. It defies logic, but he seems sincere; he is a good politician that way.

And it resonates. A decent proportion of both black and white voters, city and county voters, know him or respond to his efforts to engage. Joan Lott, a white woman in a navy, nautically themed dress and tennis shoes whom he runs into at the fair, is also a former vice chair of the Montgomery County Democratic Central Committee. When Jealous finishes chatting with her and moves on, she insists that people who are writing off Jealous’s chances are simply wrong. “I live in Leisure World, a 55-and-over community,” she says, explaining that 10,000 of the 12,000 residents are Democrats. While a lot of them may have voted for Baker in the primary, “they are solidly for the Democrats and now for Jealous.” In her community, she says, Democrats who crossed party lines to vote for Gov. Hogan in the last race are now murmuring about returning to the fold on a wave of anti-Trump sentiment. Any lingering favor for Hogan is based on his surviving cancer—and his generally non-abrasive personality, she says. “But you can’t vote for someone because he is a nice guy. You have to vote on the issues.” She rejects the notion that Jealous is too progressive for mainstream Democrats in her block of seniors. “And,” she reminds me, “they all vote.”

In the shadow of the fair’s Maryland Food shed, Jealous approaches a young black man in a red baseball cap who looks like he’s 15. “So are you old enough to vote?” he asks.

“I’m 21,” William Merchant tells him, mildly indignant but laughing. (And yes, he voted in 2016 and no, he didn’t vote in the primaries, and no, he didn’t know who Jealous was but later said he was going to google him.)

“We’ve never had a black governor before,” Jealous tells him. The young man raises his eyebrows, surprised to learn this. They fist bump. Jealous asks, “Why don’t we try it?”

Karen Houppert is a Baltimore-based freelance writer, associate director of the MA in Writing Program at Johns Hopkins University and author of Chasing Gideon: The Elusive Quest for Poor People’s Justice.

J.M. Giordano is an award-winning photojournalist based in Baltimore and co-host of the photojournalism podcast, 10 Frames Per Second. His work has been featured in American Photo magazine and has appeared in, among other outlets, The Wall St. Journal, The Guardian, The Washington Post, The Baltimore City Paper, and Rolling Stone.

0 Comments